Chapter X.

It had frequently been a source of regret to Charles, especially during that time when his mind was better able to pursue his studies, that he had not been provided with a few pencils, and a little paper, that he might occupy his lonely hours with drawing; or that he had not a slate and an account book; and now, though it is probable that he would have used them much less, he wished for them still more, because he found that the perpetual solicitude of his mind required diverting. For this purpose he frequently got a long stick, and wrote, or made figures, on the smooth sands near the shore; and as his thoughts were always wandering after his father, his writing generally consisted of letters addressed to him; and many an epistle, full of tenderness and good feeling, was, day after day, washed away by the returning waves which passed over it.

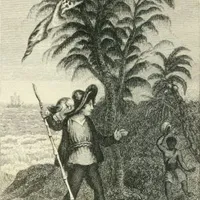

One morning, as he was going to take his station in the tree, he remarked that every word was obliterated, except "Dear papa."—"Ah!" said he, "those two words remain yet; they are the last words on the sands, and I dare say they will be the last words I shall ever utter. I remember reading in history, that Queen Mary said, 'Calais would be found written on her heart;' and if the thing were possible, 'dear papa' would now be written on mine." As Poll always considered his master's words addressed to him, he answered with, "Don't despair;" but it was in a very sleepy tone, for his master had this morning roused him before his time. With his usual consideration, Charles placed the poor bird on the first comfortable bough he found, but not until he had carefully reconnoitered the ground below, with his usual fear of serpents, so that he might be sure that Poll was safe; and then proceeded to take his regular stand on the topmost branches, from whence his shawl continued to wave.

In the course of a quarter of an hour, he saw, in the distant horizon, a dark speck, which soon increased in dimensions. Again his heart began to throb violently, for it was indeed a ship bearing to the east, and every moment shewing itself more plainly as a large complete vessel, fanned by a breeze that gently filled its sails, more and more towards the islands, yet without evincing any intention to touch at them. It was in truth far distant still; and there was no probability that if he took to his boat, this very moment, that he should be discerned, unless it steered much nearer the island; and if it did so, and should discern the flags, now visible from three points, would it not be better that he should wait where he was, and receive the strangers, who were on their way from the Cape to India, and had probably heard of the shipwreck of the Alexander, and might be on the look-out for some remnant of the crew?—"I shall be kindly received in India," said Charles, "for people cannot have forgotten my dear father; and for his sake they will send me to my mother some time; and—" at this moment, something like the sound of a piece when it flashes in the pan, struck his ear, and the words, "Misser Sharly, Misser Sharly," uttered in great trepidation, were spoken very near him. It was evident that the parrot had heard the sound, and was alarmed by it; so Charles's first care was to descend to his relief, though sorry to lose sight of the ship for a moment, since, however far removed, it was the link that tied him to his fellow-creatures. When he had descended to the lower boughs, he found Poll, to his great astonishment, fast asleep where he had left him, without a single feather ruffled or the least indication of that recent flutter which had induced him to cry out.

"Why surely, Poll, you were talking in your sleep; what could disturb you so much, my fine fellow?" said his kind master, putting out his hand to draw him into his arms.

"Misser Sharly! Misser Sharly!" screamed a voice within a little distance, and at the same moment a gun was distinctly heard.

"Am I awake, or is it all a dream?" cried the astonished, bewildered, transported boy, as, in trembling expectation he fell, rather than descended from the tree, when, lo! within fifty yards, stood a living human being!—another look convinced him it was Sambo—dear, faithful Sambo. Forgetting the snakes, and every thing else, but thankfulness to God, Charles dropped on his knees; but in another moment, he felt himself hugged, fondly hugged, to the beating breast of his faithful servant, who, between tears and laughter, half shouting, and half sobbing, cried out—"Him quike alibe! him brown as Sambo self! him lovee him Sambo same as before! Oh! happy! happy! him quike alibe—him poor fader look for him bones—no bones here." "My father, my father!" cried Charles; but he could not utter another word; his tongue clove to his mouth, his eyes seemed starting out of his head, and he looked so wild and pallid, that the joy of the poor Hindoo was suddenly turned into terror; and earnestly shaking Charles, he cried out, in a voice of distress, alternately to the long-lost object of his care, and the party who were seeking him—"Misser Sharly—Misser Sharly! Nibber go for lose him senses now, when joy come home to him heart! Here, you sailor Tom, and Ned, what for you not come carry Misser Crusoe own son in palanquin—you great rascal idles? Ha! Misser Sharly, nibber you know what we hab suffer about you. Sambo cry him eyes out—Sambo lie down to death for you!" "But where—where is my father!" "Him here—him dere—him run in ibbery place; I know well best place. Come, come—halloo, halloo! I find! I find! Sambo find!" "Ahoy, Captain Gordon, ahoy!" bawled the parrot, flapping his wings with delight, and evidently recognising his old friend Sambo, by jumping on his shoulders, even from the arms of his master, who, shaking in every limb, was rather dragged than led by Sambo towards the beach, where he began to believe that the whole scene was not an illusion of the senses, by perceiving two sailors, and an officer, standing near Capt. Gordon's grave, apparently listening to the halloos of Sambo, and the screams of the parrot. The moment they beheld Sambo, drawing forward a boy about his own size, whose appearance bespoke all the peculiarities of his situation, and who at this moment, looked more dead than alive, and conveyed the idea of his being snatched from present destruction, they set up a shout of joy, that seemed to rend the heavens, and two of them fired at the same moment. Just then Charles heard a voice cry, "Where, where is he?" That voice was surely his father's, and he thought that his figure was emerging from the trees; but he could see no more:—his head swam—his eyes failed—he fell fainting on the ground, believing that he was expiring. By degrees life revisited the pale cheek of poor Charles; and as his senses returned, he began to think that he had been afflicted with the fever, in which he had suffered from the delusions of delirious fancies. He found that he was sitting on the sands, the trees he had planted round the captain's grave were before him, and the voice of poor Poll was still ringing in his ears; but he also found that he was supported by some person's arms, and that his head was pillowed on a kind shoulder; nay more, Sambo was kneeling before him, and offering him something in a tea-cup. "You drinkee him, Misser Sharly; him do you great goodee." "That is very true, Master Crusoe," said a voice close to him. "Let Sambo hold the cup to your lips, and try to swallow the contents." At this moment a pang shot through Charles's heart—"Had he then been deceived? Was his father not here?" He took the cup, as the medium of gaining strength for farther inquiry; and the moment he had swallowed the liquid it contained, inquired—"Pray, sir, is my father living? I thought—I hoped——" "You are right in those hopes, my dear boy; your father is near you; he lives and is well; he even sees you at this very moment; but you have been so overcome by hearing his voice, that by my advice, as the surgeon of the ship that brought him, he now stands at a distance, and forbears to speak to you. You too must obey me, my dear boy; you must not suffer even your joy (natural as it is) to overcome you." "I will obey you, sir; I will try to get well, that he may be happy: but, sir, please to put me on my knees: support my hands, as the hands of Moses were supported, for if I do not thank God, I shall die again—I feel I shall." The benevolent friend instantly complied with his request, by placing him on his knees, and supporting him, as he exclaimed—"I thank thee, oh God! I thank thee that I have lived to this hour; and that my dear papa is still——" At these words he burst into a flood of tears, which relieved his loaded heart; and the surgeon then beckoned to Mr. Crusoe, who, pale and trembling, scarcely able to endure the joy and the fear of this awful scene, now took him in his arms, and holding him to his heart, thanked God for the possession of a gift so much beyond his hopes, that but a single hour before, he had (as Sambo truly said) searched the island, to find the precious remains of a child, lost to him under the most afflictive circumstances that he thought possible for a father to endure. The honest tars, though they had weathered many a rough gale without shrinking, found the scene before them affecting to the highest degree; and large tears rolled down their rough faces, as they too devoutly lifted up their hearts in thankfulness to Heaven. The surgeon alone, though a man whose feelings were as acute as his heart was kind, preserved the power to control the sensibility of those around him, as well as his own; and seeing that Sambo by turns laughed and cried, as if he were going into hysterics, he ordered him instantly to the boat, to fetch some provisions, as he thought dinner would be good for all the party; and slapping Charles on the shoulder, he exclaimed—"Come, my young friend, look up, and tell us where your stores lie; we have all come a long way to visit you, and expect that you will entertain us handsomely." Charles felt feeble and exhausted, in consequence of the agitation he had undergone; and he was so entirely content, so perfectly happy, as he laid in the arms of his father, he thought it was almost a cruelty in Mr. Parker to compel him to speak; but when he looked in his good-humoured countenance, he saw his motive for commanding attention from all parties, and immediately answered, in as gay a tone as his spirits could muster—"I have got some sea-stores on board my vessel, the Calypso, sir, which lies a short way to the leeward, and they are at your service; your men will find them in a tin case. There is island bread also, in my hut, and choice fish ready for the fire." "Very good; and a spring of pure water too, I perceive." "To which you may add a little brandy, from my ship's store; and it will be easy for you to procure a barrel of wine, for there is such a thing, fairly wedged into the sand, where it has lain ever since the time of the wreck." "And have you, my dear Charles, never been able to get to it? what a sad loss you have had!" "I think, papa, I could have got the wine out of it, though I had not strength to move the barrel; but I thought it better not to try, unless I had another fever, or something of that kind. I remembered, that I was very fond of a glass of Madeira, and I was afraid that I might be tempted to drink too much, especially when I was unhappy, and when I was hungry, in which case it would have made me tipsy, you know." "And have you never taken any of the brandy then, my dear?" "Oh yes! I have taken a small quantity very often, when I was wet through with the rain, or had been working above my strength. I took it as I did physic, to do me good; and as I dislike it very much, I had no fear of being tempted with it, as I should have been with wine." "Well done, my young philosopher!" cried Mr. Parker. "Your school has been a strange one, but it has nevertheless taught you most invaluable lessons." "So it ought, sir; for I had, in my distress, the best of books, and surely, I may add, the first of all Masters." At this moment the sailors returned, bringing with them all they had found of the highly-prized property of Charles. At this moment his father whispered—"My dear child, have you ever touched certain things which I wrapped in a handkerchief?" "Those things are all safely stowed on my person, dear father; so you will neither have the trouble to seek for them, nor the necessity of exciting attention on a subject which might be dangerous. See, papa, what curious bread I have made out of roots: I call them Crusoe carrot-cakes." Mr. Crusoe took the bread in his hand, willing to please his son by admiring it; but when he put it to his lips, it was moistened by his tears. The remembrance of those tender and unceasing cares which a fond mother had lavished on her only son, from his birth, rushed to his mind, contrasting with the many privations that dear son must have suffered; and whilst he sincerely thanked God that his beloved child had possessed strength of mind and constitution to overcome them, yet his feelings as a parent were deeply moved. Again he clasped his boy to his bosom, and asked his heart if it durst confide in its own happiness?—if his long-suffering deserted son still lived, in possession of health and understanding, with affections quickened, not impaired by absence?

On examining him, he perceived, that although very thin, he yet was considerably grown; and had proportionably increased in muscular strength. His complexion seemed embrowned to a perfect bronze on his face; but this was evidently the partial effect of continual exposure, for on taking off his jacket, his arms and neck, though without the advantage of being covered by a shirt, retained their usual colour: his hands gave decisive proof that his labour had been various. On seeing his father so much affected by surveying his person, Charles began strenuously to maintain, that although there was a time when he had been a sad figure, yet he might now be considered altogether a very respectable beau; for notwithstanding his dark curly hair was as bushy as a counsellor's wig, he knew that he had cut a great deal from it; and he conceived that his cap was really a most meritorious covering, for which he claimed great praise. When they sat down to dinner, on the sand, where there was scarcely any shade from the trees, every one allowed that his projecting head-dress was indeed an admirable contrivance: in fact, they admired and extolled every thing about him, gazing at him as if he were a living miracle; but the mind of Charles was too much occupied with joy and gratitude, to admit of any other emotion; and he was therefore happily prevented from imbibing those ideas which might have injured him, by feeding pride, and stimulating vanity.

After they had dined, the good surgeon hastened their departure (but not till he had secured what he called the drowned Madeira, which indeed proved a quarter-cask of that wine, which had been sent out to India, to be improved by the voyage); and Charles took care to gather all his goods together, not forgetting the parrot's cage, and the beautiful shawl, which was still waving on the top of his church tree; for this Sambo was despatched, as he knew the place exactly; and whilst he was gone, Charles examined his almanack trees, and counted as many notches as made seven months and eleven days, commencing with the first he could remember. Just as he had finished counting them, and Mr. Parker was drawing near, to announce that all things were ready for their departure, Sambo came running towards them, with looks of great dismay, declaring "that he had seen three serpents, from one of which he had escaped with difficulty; and having no stick in his hand, or means of defence, had been terribly frightened." "Then you did not come back the way you went surely, Sambo, or we should have seen them this morning, when you were under the tree. I told you to go and come the same way." "Yes, Misser Sharly, but him think him make one short cut. As for morning, if fifty serpents was there, Sambo see only you—you see only Sambo." "And was this danger added to the rest?" cried Mr. Crusoe, with new emotion.

"Yes, papa; it has been the worst evil I have had to contend with, at least to my own apprehension, for of all other, I feared it the most. But let us go: when we are safe on board, I will tell you, as Othello says—'All my travels' history." "I will only ask you one word now, Charles—Did you think I had purposely forsaken you?" "No, no! the thought once rushed through mind, but I banished it directly. I knew you would rather die with me than leave me; and that although it was your duty, perhaps, to prefer my mamma and my sister, if you were obliged to give up either them or me, yet I felt that you could not forsake me. No, papa! I have cried for you, as dead, or in slavery, many a time, very bitterly; but I have also cheered my heart with the hopes of seeing you again, every hour of my life, or else I could not have sustained my existence. It is true, after three months were over, I then began to expect, if you had the power of returning, you would be coming; and you will be aware, from my storing my boat, that I intended to keep a sharp look-out. It was observation of a distant ship that made me lose sight of your boat. Your vessel, I conclude, is hidden by the wood. Since I saw you, as Sambo says, I have desired to see nothing else; and never once looked for that which is so precious in my eyes—a ship bound for my own country." "My dear boy, since we parted, I have been to the Cape of Good Hope, from thence to Ceylon, and we are now bound direct to England." "Oh, joy! joy! this was more than I dared to hope for! I have got so many things for mamma, you can't think—at least for Emily." "And I have got one for them, better than all the rest—one I never hoped to take them: but we must go: you will not fret after your desolate island, my young Crusoe?" "I shall not regret its snakes nor its sorrows, father; but yet I feel someway a kind of trouble in quitting it; for I have known two very miserable nights, for want of its accommodations; and I have learnt in it more of God's word, and more of his providential goodness too, than I should have gained in any other place. So fare thee well, Island of St. Paul; thou hast got a good name, and I will not give thee a bad one." They now entered the boat, which was only a small one, the vessel to which it belonged being far inferior to that noble ship which had been stranded at the spot from which, with some difficulty, they now took their departure. Charles wished much that they could have taken his boat; but this was found impracticable; and therefore he gave up all thoughts of it: but earnestly desired the best accommodation for his parrot, which disliking the confinement of his cage, screamed incessantly—"Never despair, my dear boy!" to the great delight of the seamen.

When the boat reached the vessel, every person within the latter crowded to the deck, the moment that the figure of Charles was descried; and the most extraordinary natural curiosity ever caught, or exhibited, would have failed to awaken wonder, or excite interest, so much as he did. Every person on board knew that Mr. Crusoe had engaged the captain, by the payment of a considerable sum, to visit this island, for the purpose of seeing if his son survived; but as every day lessened the probability of such an event, and they had been detained much beyond their expectation, not one person expected that his examination of St. Paul's could produce any thing beyond the realization of his fears. As the settled melancholy of his countenance, the gentleness of his manners, and the character he bore in Bombay, made him generally beloved, every person of an amiable disposition felt for a father so situated; and from motives of delicacy and sympathy, intended to hold themselves secluded on his return, till he should have reached his own cabin, for which kind purpose, the captain promised to give them notice when the boat should be seen to leave the shore; Mr. Parker, the surgeon, determining to accompany him, for the purpose of performing the funeral ceremony over the body of poor Charles, and afterwards withdrawing the father as soon as possible from the scene. When the boat left the island, from its being deeply loaded, it came slowly, which seemed to the few who saw it, a movement in unison with the affliction of the father. On taking up his glass, Captain Linton perceived that there was another passenger, dressed in a singular helmet, gazing wistfully at the ship, as an intelligent savage might be supposed to do, whose admiration and delight were vividly expressed by his gestures; but when he saw the supposed wild youth sink down at the feet of Mr. Crusoe, lay his head in his lap, and draw the shawl, in which he was arrayed, over his face, to hide the transports, or the tears drawn from him by the novelty of his situation, he was convinced that the lost sheep was found; and the news ran through the vessel like electricity. Every heart beat with joy, every eyelid was moistened with pity; and when the young stranger stepped on board, a shout of welcome and exultation ran through the ship, and seemed to swell the very sails with triumph. Hands were held out on all sides—voices in all tones uttered congratulations; and as there were several ladies among the passengers, Charles almost believed that his mother was addressing him, and in the confusion of pleasure, felt bewildered and overpowered.

By the advice of Mr. Parker, both father and son, for this evening, retired to the cabin of the former, into which suitable accommodation for the stranger was speedily handed, together with Poll, who, like his master, had not all at once the power of meeting his new acquaintance with composure. Charles intended to remain perfectly quiet for some time, but he could not forbear to go on deck, and gaze upon the island, so long as it remained in view, wondering at his own strange sensation, in which something like sorrow, that he should never see it more, mingled with pleasure for his escape from it, as a prison condemning him to solitary confinement, to fear, and to want.

When the fond son returned to the cabin, much as he desired to know every thing that related to his father, and to Sambo also (who never lost sight of his recovered young master five minutes at a time), he yet complied willingly with the advice he had received from Mr. Parker, to ask no questions, or relate any adventures for that night, being well aware that he was now much in the same state of exhaustion from his surprise and happiness, that he had repeatedly been from his misery and disappointment. But there was one thing he could not deny himself, which was that of closely nestling to his father, and either holding him by the hand or the clothes, as if he feared to lose him for a moment. When thus seated, with his faithful Sambo before his eyes, and poor Poll, now well fed, and sleeping by his side, and the remembrance that he was sailing towards dear England, which contained another parent and sister, full on his mind, he wanted nothing more to render him the happiest boy on the face of the wide earth.

The following day he became acquainted with the reason of his father's mysterious disappearance; but as Mr. Crusoe's narrative was frequently interrupted by the inquiries of his anxious son, we will comprise the circumstances in the following chapter.