Chapter 8 Part 2

“I'm going to drain the pool today, Mr. Gatsby. Leaves'll start falling pretty soon, and then there's always trouble with the pipes.”

“Don't do it today,” Gatsby answered. He turned to me apologetically. “You know, old sport, I've never used that pool all summer?”

I looked at my watch and stood up.

“Twelve minutes to my train.”

I didn't want to go to the city. I wasn't worth a decent stroke of work, but it was more than that—I didn't want to leave Gatsby. I missed that train, and then another, before I could get myself away.

“I'll call you up,” I said finally.

“Do, old sport.”

“I'll call you about noon.”

We walked slowly down the steps.

“I suppose Daisy'll call too.” He looked at me anxiously, as if he hoped I'd corroborate this.

“I suppose so.”

“Well, goodbye.”

We shook hands and I started away. Just before I reached the hedge I remembered something and turned around.

“They're a rotten crowd,” I shouted across the lawn. “You're worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

I've always been glad I said that. It was the only compliment I ever gave him, because I disapproved of him from beginning to end. First he nodded politely, and then his face broke into that radiant and understanding smile, as if we'd been in ecstatic cahoots on that fact all the time. His gorgeous pink rag of a suit made a bright spot of colour against the white steps, and I thought of the night when I first came to his ancestral home, three months before. The lawn and drive had been crowded with the faces of those who guessed at his corruption—and he had stood on those steps, concealing his incorruptible dream, as he waved them goodbye.

I thanked him for his hospitality. We were always thanking him for that—I and the others.

“Goodbye,” I called. “I enjoyed breakfast, Gatsby.”

Up in the city, I tried for a while to list the quotations on an interminable amount of stock, then I fell asleep in my swivel-chair. Just before noon the phone woke me, and I started up with sweat breaking out on my forehead. It was Jordan Baker; she often called me up at this hour because the uncertainty of her own movements between hotels and clubs and private houses made her hard to find in any other way. Usually her voice came over the wire as something fresh and cool, as if a divot from a green golf-links had come sailing in at the office window, but this morning it seemed harsh and dry.

“I've left Daisy's house,” she said. “I'm at Hempstead, and I'm going down to Southampton this afternoon.”

Probably it had been tactful to leave Daisy's house, but the act annoyed me, and her next remark made me rigid.

“You weren't so nice to me last night.”

“How could it have mattered then?”

Silence for a moment. Then:

“However—I want to see you.”

“I want to see you, too.”

“Suppose I don't go to Southampton, and come into town this afternoon?”

“No—I don't think this afternoon.”

“Very well.”

“It's impossible this afternoon. Various—”

We talked like that for a while, and then abruptly we weren't talking any longer. I don't know which of us hung up with a sharp click, but I know I didn't care. I couldn't have talked to her across a tea-table that day if I never talked to her again in this world.

I called Gatsby's house a few minutes later, but the line was busy. I tried four times; finally an exasperated central told me the wire was being kept open for long distance from Detroit. Taking out my timetable, I drew a small circle around the three-fifty train. Then I leaned back in my chair and tried to think. It was just noon.

When I passed the ash-heaps on the train that morning I had crossed deliberately to the other side of the car. I supposed there'd be a curious crowd around there all day with little boys searching for dark spots in the dust, and some garrulous man telling over and over what had happened, until it became less and less real even to him and he could tell it no longer, and Myrtle Wilson's tragic achievement was forgotten. Now I want to go back a little and tell what happened at the garage after we left there the night before.

They had difficulty in locating the sister, Catherine. She must have broken her rule against drinking that night, for when she arrived she was stupid with liquor and unable to understand that the ambulance had already gone to Flushing. When they convinced her of this, she immediately fainted, as if that was the intolerable part of the affair. Someone, kind or curious, took her in his car and drove her in the wake of her sister's body.

Until long after midnight a changing crowd lapped up against the front of the garage, while George Wilson rocked himself back and forth on the couch inside. For a while the door of the office was open, and everyone who came into the garage glanced irresistibly through it. Finally someone said it was a shame, and closed the door. Michaelis and several other men were with him; first, four or five men, later two or three men. Still later Michaelis had to ask the last stranger to wait there fifteen minutes longer, while he went back to his own place and made a pot of coffee. After that, he stayed there alone with Wilson until dawn.

About three o'clock the quality of Wilson's incoherent muttering changed—he grew quieter and began to talk about the yellow car. He announced that he had a way of finding out whom the yellow car belonged to, and then he blurted out that a couple of months ago his wife had come from the city with her face bruised and her nose swollen.

But when he heard himself say this, he flinched and began to cry “Oh, my God!” again in his groaning voice. Michaelis made a clumsy attempt to distract him.

“How long have you been married, George? Come on there, try and sit still a minute, and answer my question. How long have you been married?”

“Twelve years.”

“Ever had any children? Come on, George, sit still—I asked you a question. Did you ever have any children?”

The hard brown beetles kept thudding against the dull light, and whenever Michaelis heard a car go tearing along the road outside it sounded to him like the car that hadn't stopped a few hours before. He didn't like to go into the garage, because the work bench was stained where the body had been lying, so he moved uncomfortably around the office—he knew every object in it before morning—and from time to time sat down beside Wilson trying to keep him more quiet.

“Have you got a church you go to sometimes, George? Maybe even if you haven't been there for a long time? Maybe I could call up the church and get a priest to come over and he could talk to you, see?”

“Don't belong to any.”

“You ought to have a church, George, for times like this. You must have gone to church once. Didn't you get married in a church? Listen, George, listen to me. Didn't you get married in a church?”

“That was a long time ago.”

The effort of answering broke the rhythm of his rocking—for a moment he was silent. Then the same half-knowing, half-bewildered look came back into his faded eyes.

“Look in the drawer there,” he said, pointing at the desk.

“Which drawer?”

“That drawer—that one.”

Michaelis opened the drawer nearest his hand. There was nothing in it but a small, expensive dog-leash, made of leather and braided silver. It was apparently new.

“This?” he inquired, holding it up.

Wilson stared and nodded.

“I found it yesterday afternoon. She tried to tell me about it, but I knew it was something funny.”

“You mean your wife bought it?”

“She had it wrapped in tissue paper on her bureau.”

Michaelis didn't see anything odd in that, and he gave Wilson a dozen reasons why his wife might have bought the dog-leash. But conceivably Wilson had heard some of these same explanations before, from Myrtle, because he began saying “Oh, my God!” again in a whisper—his comforter left several explanations in the air.

“Then he killed her,” said Wilson. His mouth dropped open suddenly.

“Who did?”

“I have a way of finding out.”

“You're morbid, George,” said his friend. “This has been a strain to you and you don't know what you're saying. You'd better try and sit quiet till morning.”

“He murdered her.”

“It was an accident, George.”

Wilson shook his head. His eyes narrowed and his mouth widened slightly with the ghost of a superior “Hm!”

“I know,” he said definitely. “I'm one of these trusting fellas and I don't think any harm to nobody, but when I get to know a thing I know it. It was the man in that car. She ran out to speak to him and he wouldn't stop.”

Michaelis had seen this too, but it hadn't occurred to him that there was any special significance in it. He believed that Mrs. Wilson had been running away from her husband, rather than trying to stop any particular car.

“How could she of been like that?”

“She's a deep one,” said Wilson, as if that answered the question. “Ah-h-h—”

He began to rock again, and Michaelis stood twisting the leash in his hand.

“Maybe you got some friend that I could telephone for, George?”

This was a forlorn hope—he was almost sure that Wilson had no friend: there was not enough of him for his wife. He was glad a little later when he noticed a change in the room, a blue quickening by the window, and realized that dawn wasn't far off. About five o'clock it was blue enough outside to snap off the light.

Wilson's glazed eyes turned out to the ash-heaps, where small grey clouds took on fantastic shapes and scurried here and there in the faint dawn wind.

“I spoke to her,” he muttered, after a long silence. “I told her she might fool me but she couldn't fool God. I took her to the window”—with an effort he got up and walked to the rear window and leaned with his face pressed against it—“and I said ‘God knows what you've been doing, everything you've been doing. You may fool me, but you can't fool God!' ”

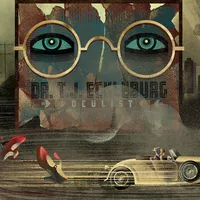

Standing behind him, Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, which had just emerged, pale and enormous, from the dissolving night.

“God sees everything,” repeated Wilson.

“That's an advertisement,” Michaelis assured him. Something made him turn away from the window and look back into the room. But Wilson stood there a long time, his face close to the window pane, nodding into the twilight.

By six o'clock Michaelis was worn out, and grateful for the sound of a car stopping outside. It was one of the watchers of the night before who had promised to come back, so he cooked breakfast for three, which he and the other man ate together. Wilson was quieter now, and Michaelis went home to sleep; when he awoke four hours later and hurried back to the garage, Wilson was gone.

His movements—he was on foot all the time—were afterward traced to Port Roosevelt and then to Gad's Hill, where he bought a sandwich that he didn't eat, and a cup of coffee. He must have been tired and walking slowly, for he didn't reach Gad's Hill until noon. Thus far there was no difficulty in accounting for his time—there were boys who had seen a man “acting sort of crazy,” and motorists at whom he stared oddly from the side of the road. Then for three hours he disappeared from view. The police, on the strength of what he said to Michaelis, that he “had a way of finding out,” supposed that he spent that time going from garage to garage thereabout, inquiring for a yellow car. On the other hand, no garage man who had seen him ever came forward, and perhaps he had an easier, surer way of finding out what he wanted to know. By half-past two he was in West Egg, where he asked someone the way to Gatsby's house. So by that time he knew Gatsby's name.