Class 5: Vikings, Slavers, Lawgivers: The Kyiv State (2)

that we'll be talking about next lecture,

that was an acceptable answer

all the way until the 14th century.

They did much more enslaving

than people did, enslaving of their people.

They stayed pagans for a very long time.

It worked for them.

But what I mean by the math is that Christians

are not supposed to enslave Christians.

Muslims are not supposed to enslave Muslims.

When Christian and Muslim states fight,

they'll do exchanges and so on.

But so long as you're a pagan,

you're fair game for everyone.

And so territorially,

as Christianity spreads into Europe,

there are more and more of them,

and fewer and fewer of you, right?

So every time some other state converts

to Christianity, the math is getting worse

for you as a pagan.

There are more and more situations

where you can be enslaved,

and fewer and fewer situations

where you're gonna find it practicable

to enslave other people.

It's just kind of a general logic.

Okay, I realize that's a strange answer

to the question of what is Christianity,

but what is Christianity

is fundamentally a way of joining a Christian order

of states in which you're not supposed

to enslave the other people,

who are also subjects of a Christian order of state.

More specifically, Christianity means

these two varieties of Christianity.

So when I say that Christianity is a power

and that it brings with it recognition,

okay, recognition by whom?

Recognition by the Franks

coming from the west,

or recognition from the Byzantines

coming from the south?

As you know, the Franks and the Byzantines

have two different accounts of what happened

to the Roman Empire.

It fell, and we rebuilt it.

Very beautiful. That's the Franks.

Or it never fell. We are it.

Also very beautiful.

That's the Byzantines.

So these are two relationships

to the classical world, but more importantly,

these are two powers

that are moving into Eastern Europe.

The Franks, so let's get some more detail about this.

The great leader of the Franks.

So this is not a course in French history,

but you'll find that we have to talk about

what the French, 'cause France, frankly,

was very important, okay?

So we will keep coming back to things

that happened in what's now France and Germany

because France and Germany are very important.

The turning point here,

the coronation of Charlemagne

as king of the Franks on Christmas Day

of the year 800.

Very easy to.

He calls it the.

(indistinct)

He calls it the restoration of empire.

Christmas Day, 800.

Charlemagne just means Charles the Great.

And incidentally, the word Charles.

So there's now another king called Charles, right?

Am I up on my news?

So the word Charles

in Slavic languages.

Well, how do you say like Charles

in a Slavic language?

Any Slavic language.

Hm? - Karel.

- Karel. Karel is good.

Okay, so that name Charles

becomes the Slavic word,

or a Slavic word, for king,

which is, I mean, that's kind of impressive, right?

Like, I mean, that's the sort of thing,

like if you were a rapper,

you would want your name to become

the word for king, right?

And I'm just gonna say now,

no rapper is ever going to achieve that, right?

I mean, no rapper is ever gonna outdo Charlemagne

on this front, I don't think.

Okay.

I mean, I'm just, I'm happy to have

that prediction on tape.

So Charles, in French,

Charles, Charles, becomes Karl

or Karol in Slavic languages,

which is the word for king.

In Polish, it's Karol.

Ukrainian, Karl.

So the very idea of kingship

is coming from this kingdom

of the Franks established in 800.

And it is a new model state.

It's the model state

which is then going to prevail in Europe,

very importantly, where the king accepts

that he is a Christian ruler,

and he accepts, for example,

that he can be crowned by a pope,

but he's not subordinate to the pope.

Whereas in the south, in Byzantium,

the idea of kingship is going to be very different.

The idea is that

the secular ruler and the religious power

are very much in alignment.

We'll return to that.

So the word for ruler in much of Eastern Europe

is czar, which comes from Caesar, right,

which comes from Rome.

That's the Byzantine tradition.

So the very words that you have

for the supreme leader in a political system

are coming from these two rival powers.

Okay, so what can we say about the south?

We've already said a lot of it.

Byzantium, the Byzantine empire.

Capital in Constantinople,

which is today Istanbul.

There's a song by They Might Be Giants about that,

which I'm sure those of you who are into oldies know.

It's been the capital of the Roman Empire

since the 4th century.

From the point of view of Byzantium,

there's an unbroken succession

of legitimate Roman emperors

the entire time.

They refer to themselves as the Romans.

They do so speaking Greek.

That's Byzantium.

That city, Constantinople,

is unparalleled in the Europe of the time.

It's 10, 20, 30 times bigger than.

It's 30 times bigger than Paris.

You know, we don't know exactly how big,

but maybe something like a million people.

A tremendous scale of a city for the time.

And gloriously beautiful in a way

which no European city

can vaguely think of rivaling.

And still worth a visit, by the way.

Still lovely, Istanbul.

Worth a visit.

I was there on my honeymoon.

It was worth it. Okay.

So the differences between the Franks

and the Byzantines.

We've listed several of them.

Two claims to the Roman inheritance, right?

Two varieties of Christianity,

although the theology's not so important.

Two different relationships between state

and secular power, where in Byzantium,

state and, sorry, state and religious power,

state and spiritual power

are much more carefully lined up.

Two relationships between lords and vassals.

In the Frankish political tradition,

the vassals are gonna be lined up

in something which we think of as a feudal system,

where they have the right to property

and have a certain amount of autonomy.

That is going to be less true in Byzantium.

But both of them are in Europe,

and both of them are in a Europe

which is pushing into the pagan world.

There are the Scandinavians to be converted,

there are the Celts to be converted

and there are the Slavs to be converted.

The Celts.

The Celts, you know, the Scots,

the Irish, they're out of reach of Byzantium.

The Scandinavians, it turns out,

are also out of reach of Byzantium,

except for the Scandinavians who travel to Kyiv,

which we're gonna get to,

but the Slavs are not out of reach.

And the Slavs are the biggest group,

the Slavs are the biggest prize,

and the Slavs are an object

of direct and explicit competition

between these two powers.

Byzantium is already there,

with its missionary activity.

We mentioned Cyril and Methodius.

That's an example of missionary activity from Byzantium.

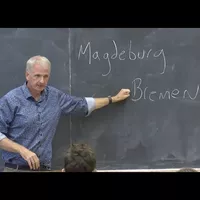

The Franks set up an archbishopric

in the German city of Magdeburg

in 962.

And that is a kind of outpost

of missionary activity.

So when you think of these archbishoprics.

So the way that the Christian Church in the West

is set up, there are bishops, and the bishop

of Rome is the highest bishop,

and he's known as the pope, right?

Underneath the pope, there are archbishops,

who have territory.

Underneath the archbishops, there are bishops,

and they have territory.

Underneath the bishops, there are priests,

and the priests have territory.

And that territory is known as a parish.

It's all beautifully organized.

But when you think of these archbishoprics,

you should be thinking of imperial expansion, too.

Magdeburg is about imperial expansion to the west.

And Bremen, by the way,

is about imperial expansion to the north.

So when the German speakers are trying to convert

the Scandinavians, they're doing it from Bremen.

In the meantime, people are also trying to convert

the Scandinavians from England.

But the Scandinavians are out of reach.

I just mentioned this as another example.

This is also a nice place to visit.

The Scandinavians are out of reach, but the Slavs are not.

Okay.

This all hooks together.

It all connects when everyone.

And, you know, if you try to think, like,

what is the one thing which causes this?

Things are always connecting, right?

So if I say, "What does religion have to do with it?"

Well, religion has to do with creating a state,

but it also has to do with not being enslaved,

and eventually, it has to do with what people

actually believe, and these things are all connected.

If I say, at this part of the lecture,

"What do the Vikings have to do with it?"

The Vikings come in

to the history of both the Franks

and the Byzantines, right?

Because this period that we're talking about

is the Viking age.

The Viking age begins in 793.

That's when the Vikings first make themselves known.

And if you say the Viking age,

it's like now we cut

to a completely different movie, right?

We forget everything else.

It's just the wooden ships

with their beautiful brows and the burly men

and the beards and the horns

and the throwing the spears over the enemy,

which probably is a myth, and the berserker thing,

which is also probably a myth.

But we're cutting to a completely different story, right?

And that's what we can't do,

because the Viking age is happening simultaneously

with the expansion of the Franks

and with the expansion of the Byzantines,

and it's related to these two things.

It is the expansion of the Franks

which probably provokes the Vikings

to test out their own naval technology

by plundering the Franks. (laughs)

And then, realizing they can do this,

they can get down rivers,

they can do interesting things,

they can also go out to sea and do interesting things.

So the Vikings are probably best understood

as a reaction to Charlemagne.

And in their reaction,

as they realize that there are an awful lot

of rivers they could go down in river in Europe,

and there's an awful lot that could be plundered,

or looking at it more sympathetically,

trade routes to be established,

this brings them to Eastern Europe

and to Byzantium.

And I know you guys are wondering why

I keep obsessing about the mountains

and the rivers and all these things

that don't matter anymore because the internet,

I know, but you can't figure out

what the Vikings are up to

without knowing where the rivers are.

The Vikings are trying to get from north to south,

because they're trying to make a huge amount of money.

There's a lot of silver down there with the Arabs,

and they can get that silver,

and they can bury it in big hoards,

which is what they like to do, for mysterious reasons.

It's really great for archeologists and for historians,

because we can say, "Okay, look,

"here is a hoard of coins,

"which were clearly minted

"in an Arab-speaking place at this time.

"But look, it's in Northwestern Russia."

And how do we explain that?

And we explain it with the Vikings, right?

So the Vikings are trying to make a lot of money

by trading from north to south.

And they do that with their technology,

which is the boat,

but they have to find a way, right?

So they try to get down with the Volga,

which doesn't work.

They try to get down with the Dnipro,

which does work, right, the river which runs

through the middle of Ukraine.

They eventually find their way down

and they eventually start to trade.

But this means that our Vikings, these Vikings,

who are known as the Rus',

these Vikings come into contact

with Byzantium.

They come into contact with Byzantium, right?

Byzantium is the big economic