CHAPTER XXXII. SHRINE OF SEVEN LAMPS

Never can I forget that nightmare apartment, that efreet's hall. It was identical in shape with the room of the adjoining house through which I had come, but its walls were draped in somber black and a dead black carpet covered the entire floor. A golden curtain—similar to that which concealed me—broke the somber expanse of the end wall to my right, and the door directly opposite my hiding-place was closed.

Across the gold curtain, wrought in glittering black, were seven characters, apparently Chinese; before it, supported upon seven ebony pedestals, burned seven golden lamps; whilst, dotted about the black carpet, were seven gold-lacquered stools, each having a black cushion set before it. There was no sign of the marmoset; the incredible room of black and gold was quite empty, with a sort of stark emptiness that seemed to oppress my soul.

Close upon the booming of the gong followed a sound of many footsteps and a buzz of subdued conversation. Keeping well back in the welcome shadow I watched, with bated breath, the opening of the door immediately opposite.

The outer sides of its leaves proved to be of gold, and one glimpse of the room beyond awoke a latent memory and gave it positive form. I had been in this house before; it was in that room with the golden door that I had had my memorable interview with the mandarin Ki-Ming! My excitement grew more and more intense.

Singly, and in small groups, a number of Orientals came in. All wore European, or semi-European garments, but I was enabled to identify two for Chinamen, two for Hindus and three for Burmans. Other Asiatics there were, also, whose exact place among the Eastern races I could not determine; there was at least one Egyptian and there were several Eurasians; no women were present.

Standing grouped just within the open door, the gathering of Orientals kept up a ceaseless buzz of subdued conversation; then, abruptly, stark silence fell, and through a lane of bowed heads, Ki-Ming, the famous Chinese diplomat, entered, smiling blandly, and took his seat upon one of the seven golden stools. He wore the picturesque yellow robe, trimmed with marten fur, which I had seen once before, and he placed his pearl-encircled cap, surmounted by the coral ball denoting his rank, upon the black cushion beside him.

Almost immediately afterward entered a second and even more striking figure. It was that of a Lama monk! He was received with the same marks of deference which had been accorded the mandarin; and he seated himself upon another of the golden stools.

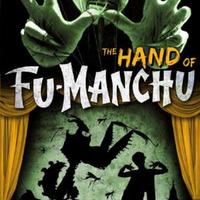

Silence, a moment of hushed expectancy, and … yellow-robed, immobile, his wonderful, evil face emaciated by illness, but his long, magnetic eyes blazing greenly, as though not a soul but an elemental spirit dwelt within that gaunt, high-shouldered body, Dr. Fu-Manchu entered, slowly, leaning upon a heavy stick!

The realities seemed to be slipping from me; I could not believe that I looked upon a material world. This had been a night of wonders, having no place in the life of a sane, modern man, but belonging to the days of the jinn and the Arabian necromancers.

Fu-Manchu was greeted by a universal raising of hands, but in complete silence. He also wore a cap surmounted by a coral ball, and this he placed upon one of the black cushions set before a golden stool. Then, resting heavily upon his stick, he began to speak—in French!

As on listens to a dream-voice, I listened to that, alternately gutteral and sibilant, of the terrible Chinese doctor. He was defending himself! With what he was charged by his sinister brethren I knew not nor could I gather from his words, but that he was rendering account of his stewardship became unmistakable. Scarce crediting my senses, I heard him unfold to his listeners details of crimes successfully perpetrated, and with the results of some of these I was but too familiar; other there were in the ghastly catalogue which had been accomplished secretly. Then my blood froze with horror. My own name was mentioned—and that of Nayland Smith! We two stood in the way of the coming of one whom he called the Lady of the Si-Fan, in the way of Asiatic supremacy.

A fantastic legend once mentioned to me by Smith, of some woman cherished in a secret fastness of Hindustan who was destined one day to rule the world, now appeared, to my benumbed senses, to be the unquestioned creed of the murderous, cosmopolitan group known as the Si-Fan! At every mention of her name all heads were bowed in reverence.

Dr. Fu-Manchu spoke without the slightest trace of excitement; he assured his auditors of his fidelity to their cause and proposed to prove to them that he enjoyed the complete confidence of the Lady of the Si-Fan.

And with every moment that passed the giant intellect of the speaker became more and more apparent. Years ago Nayland Smith had asssure me that Dr. Fu-Manchu was a linguist who spoke with almost equal facility in any of th civilized languages and in most of the barbaric; now the truth of this was demonstrated. For, following some passage which might be susceptible of misconstruction, Fu-Manchu would turn slightly, and elucidate his remarks, addressing a Chinaman in Chinese, a Hindu in Hindustanee, or an Egyptian in Arabic.

His auditors were swayed by the magnetic personality of the speaker, as reeds by a breeze; and now I became aware of a curious circumstance. Either because they and I viewed the character of this great and evil man from a widely dissimilar aspect, or because, my presence being unknown to him, I remained outside the radius of his power, it seemed to me that these members of the evidently vast organization known as the Si-Fan were dupes, to a man, of the Chinese orator! It seemed to me that he used them as an instrument, playing upon their obvious fanaticism, string by string, as a player upon an Eastern harp, and all the time weaving harmonies to suit some giant, incredible scheme of his own—a scheme over and beyond any of which they had dreamed, in the fruition whereof they had no part—of the true nature and composition of which they had no comprehension.

"Not since the day of the first Yuan Emperor," said Fu-Manchu sibilantly, "has Our Lady of the Si-Fan—to look upon upon whom, unveiled, is death—crossed the sacred borders. To-day I am a man supremely happy and honored above my deserts. You shall all partake with me of that happiness, that honor…." Again the gong sounded seven times, and a sort of magnetic thrill seemed to pass throughout the room. There followed a faint, musical sound, like the tinkle of a silver bell.

All heads were lowered, but all eyes upturned to the golden curtain. Literally holding my breath, in those moments of intense expectancy, I watched the draperies parted from the center and pulled aside by unseen agency.

A black covered dais was revealed, bearing an ebony chair. And seated in the chair, enveloped from head to feet in a shimmering white veil, was a woman. A sound like a great sigh arose from the gathering. The woman rose slowly to her feet, and raised her arms, which were exquisitely formed, and of the uniform hue of old ivory, so that the veil fell back to her shoulders, revealing the green snake bangle which she wore. She extended her long, slim hands as if in benediction; the silver bell sounded … and the curtain dropped again, entirely obscuring the dais!

Frankly, I thought myself mad; for this "lady of the Si-Fan" was none other than my mysterious traveling companion! This was some solemn farce with which Fu-Manchu sought to impress his fanatical dupes. And he had succeeded; they were inspired, their eyes blazed. Here were men capable of any crime in the name of the Si-Fan!

Every face within my ken I had studied individually, and now slowly and cautiously I changed my position, so that a group of three members standing immediately to the right of the door came into view. One of them—a tall, spare, and closely bearded man whom I took for some kind of Hindu—had removed his gaze from the dais and was glancing furtively all about him. Once he looked in my direction, and my heart leapt high, then seemed to stop its pulsing.

An overpowering consciousness of my danger came to me; a dim envisioning of what appalling fate would be mine in the event of discovery. As those piercing eyes were turned away again, I drew back, step my step.

Dropping upon my knees, I began to feel for the gap in the conservatory wall. The desire to depart from the house of the Si-Fan was become urgent. Once safely away, I could take the necessary steps to ensure the apprehension of the entire group. What a triumph would be mine!

I found the opening without much difficulty and crept through into the empty house. The vague light which penetrated the linen blinds served to show me the length of the empty, tiled apartment. I had actually reached the French window giving access to the drawing-room, when—the skirl of a police whistle split the stillness … and the sound came from the house which I had just quitted!

To write that I was amazed were to achieve the banal. Rigid with wonderment I stood, and clutched at the open window. So I was standing, a man of stone, when the voice, the high-pitched, imperious, unmistakable voice of Nayland Smith, followed sharply upon the skirl of the whistle:—

"Watch those French windows, Weymouth! I can hold the door!" Like a lightning flash it came to me that the tall Hindu had been none other than Smith disguised. From the square outside came a sudden turmoil, a sound of racing feet, of smashing glass, of doors burst forcibly open. Palpably, the place was surrounded; this was an organized raid.

Irresolute, I stood there in the semi-gloom—inactive from amaze of it all—whilst sounds of a tremendous struggle proceeded from the square gap in the partition.

"Lights!" rose a cry, in Smith's voice again—"they have cut the wires!" At that I came to my senses. Plunging my hand into my pocket, I snatched out the electric lamp … and stepped back quickly into the utter gloom of the room behind me.

Some one was crawling through the aperture into the conservatory!

As I watched I saw him, in the dim light, stoop to replace the movable panel. Then, tapping upon the tiled floor as he walked, the fugitive approached me. He was but three paces from the French window when I pressed the button of my lamp and directed its ray fully upon his face.

"Hands up!" I said breathlessly. "I have you covered, Dr. Fu-Manchu!"