Chapter 4. The Little Attic Room

Miss Polly Harrington did not rise to meet her niece. She looked up from her book, it is true, as Nancy and the little girl appeared in the sitting-room doorway, and she held out a hand with "duty" written large on every coldly extended finger. "How do you do, Pollyanna? I--" She had no chance to say more. Pollyanna, had fairly flown across the room and flung herself into her aunt's scandalized, unyielding lap. "Oh, Aunt Polly, Aunt Polly, I don't know how to be glad enough that you let me come to live with you," she was sobbing. "You don't know how perfectly lovely it is to have you and Nancy and all this after you've had just the Ladies' Aid!" "Very likely--though I've not had the pleasure of the Ladies' Aid's acquaintance," rejoined Miss Polly, stiffly, trying to unclasp the small, clinging fingers, and turning frowning eyes on Nancy in the doorway. "Nancy, that will do. You may go. Pollyanna, be good enough, please, to stand erect in a proper manner. I don't know yet what you look like." Pollyanna drew back at once, laughing a little hysterically.

"No, I suppose you don't; but you see I'm not very much to took at, anyway, on account of the freckles. Oh, and I ought to explain about the red gingham and the black velvet basque with white spots on the elbows. I told Nancy how father said--" "Yes; well, never mind now what your father said," interrupted Miss Polly, crisply. "You had a trunk, I presume?" "Oh, yes, indeed, Aunt Polly. I've got a beautiful trunk that the Ladies' Aid gave me. I haven't got so very much in it--of my own, I mean. The barrels haven't had many clothes for little girls in them lately; but there were all father's books, and Mrs. White said she thought I ought to have those. You see, father--" "Pollyanna," interrupted her aunt again, sharply, "there is one thing that might just as well be understood right away at once; and that is, I do not care to have you keep talking of your father to me." The little girl drew in her breath tremulously.

"Why, Aunt Polly, you--you mean--" She hesitated, and her aunt filled the pause. "We will go up-stairs to your room. Your trunk is already there, I presume. I told Timothy to take it up--if you had one. You may follow me, Pollyanna." Without speaking, Pollyanna turned and followed her aunt from the room. Her eyes were brimming with tears, but her chin was bravely high.

"After all, I--I reckon I'm glad she doesn't want me to talk about father," Pollyanna was thinking. "It'll be easier, maybe--if I don't talk about him. Probably, anyhow, that is why she told me not to talk about him." And Pollyanna, convinced anew of her aunt's "kindness," blinked off the tears and looked eagerly about her. She was on the stairway now. Just ahead, her aunt's black silk skirt rustled luxuriously. Behind her an open door allowed a glimpse of soft-tinted rugs and satin-covered chairs. Beneath her feet a marvellous carpet was like green moss to the tread. On every side the gilt of picture frames or the glint of sunlight through the filmy mesh of lace curtains flashed in her eyes.

"Oh, Aunt Polly, Aunt Polly," breathed the little girl, rapturously; "what a perfectly lovely, lovely house! How awfully glad you must be you're so rich!" "Polly anna! " ejaculated her aunt, turning sharply about as she reached the head of the stairs. "I'm surprised at you--making a speech like that to me!" "Why, Aunt Polly, aren't you?" queried Pollyanna, in frank wonder.

"Certainly not, Pollyanna. I hope I could not so far forget myself as to be sinfully proud of any gift the Lord has seen fit to bestow upon me," declared the lady; "certainly not, of riches! " Miss Polly turned and walked down the hall toward the attic stairway door. She was glad, now, that she had put the child in the attic room. Her idea at first had been to get her niece as far away as possible from herself, and at the same time place her where her childish heedlessness would not destroy valuable furnishings. Now--with this evident strain of vanity showing thus early--it was all the more fortunate that the room planned for her was plain and sensible, thought Miss Polly.

Eagerly Pollyanna's small feet pattered behind her aunt. Still more eagerly her big blue eyes tried to look in all directions at once, that no thing of beauty or interest in this wonderful house might be passed unseen. Most eagerly of all her mind turned to the wondrously exciting problem about to be solved: behind which of all these fascinating doors was waiting now her room--the dear, beautiful room full of curtains, rugs, and pictures, that was to be her very own? Then, abruptly, her aunt opened a door and ascended another stairway.

There was little to be seen here. A bare wall rose on either side. At the top of the stairs, wide reaches of shadowy space led to far corners where the roof came almost down to the floor, and where were stacked innumerable trunks and boxes. It was hot and stifling, too. Unconsciously Pollyanna lifted her head higher--it seemed so hard to breathe. Then she saw that her aunt had thrown open a door at the right.

"There, Pollyanna, here is your room, and your trunk is here, I see. Have you your key?" Pollyanna nodded dumbly. Her eyes were a little wide and frightened.

Her aunt frowned.

"When I ask a question, Pollyanna, I prefer that you should answer aloud not merely with your head." "Yes, Aunt Polly." "Thank you; that is better. I believe you have everything that you need here," she added, glancing at the well-filled towel rack and water pitcher. "I will send Nancy up to help you unpack. Supper is at six o'clock," she finished, as she left the room and swept down-stairs. For a moment after she had gone Pollyanna stood quite still, looking after her. Then she turned her wide eyes to the bare wall, the bare floor, the bare windows. She turned them last to the little trunk that had stood not so long before in her own little room in the far-away Western home. The next moment she stumbled blindly toward it and fell on her knees at its side, covering her face with her hands.

Nancy found her there when she came up a few minutes later.

"There, there, you poor lamb," she crooned, dropping to the floor and drawing the little girl into her arms. "I was just a-fearin! I'd find you like this, like this." Pollyanna shook her head.

"But I'm bad and wicked, Nancy--awful wicked," she sobbed. "I just can't make myself understand that God and the angels needed my father more than I did." "No more they did, neither," declared Nancy, stoutly. "Oh-h!-- Nancy! " The burning horror in Pollyanna's eyes dried the tears. Nancy gave a shamefaced smile and rubbed her own eyes vigorously.

"There, there, child, I didn't mean it, of course," she cried briskly. "Come, let's have your key and we'll get inside this trunk and take our your dresses in no time, no time." Somewhat tearfully Pollyanna produced the key.

"There aren't very many there, anyway," she faltered. "Then they're all the sooner unpacked," declared Nancy. Pollyanna gave a sudden radiant smile.

"That's so! I can be glad of that, can't I?" she cried.

Nancy stared.

"Why, of--course," she answered a little uncertainly. Nancy's capable hands made short work of unpacking the books, the patched undergarments, and the few pitifully unattractive dresses. Pollyanna, smiling bravely now, flew about, hanging the dresses in the closet, stacking the books on the table, and putting away the undergarments in the bureau drawers.

"I'm sure it--it's going to be a very nice room. Don't you think so?" she stammered, after a while.

There was no answer. Nancy was very busy, apparently, with her head in the trunk. Pollyanna, standing at the bureau, gazed a little wistfully at the bare wall above.

"And I can be glad there isn't any looking-glass here, too, 'cause where there isn't any glass I can't see my freckles." Nancy made a sudden queer little sound with her mouth--but when Pollyanna turned, her head was in the trunk again. At one of the windows, a few minutes later, Pollyanna gave a glad cry and clapped her hands joyously.

"Oh, Nancy, I hadn't seen this before," she breathed. "Look--'way off there, with those trees and the houses and that lovely church spire, and the river shining just like silver. Why, Nancy, there doesn't anybody need any pictures with that to look at. Oh, I'm so glad now she let me have this room!" To Pollyanna's surprise and dismay, Nancy burst into tears. Pollyanna hurriedly crossed to her side.

"Why, Nancy, Nancy--what is it?" she cried; then, fearfully: "This wasn't-- your room, was it?" "My room!" stormed Nancy, hotly, choking back the tears. "If you ain't a little angel straight from Heaven, and if some folks don't eat dirt before--Oh, land! there's her bell!" After which amazing speech, Nancy sprang to her feet, dashed out of the room, and went clattering down the stairs.

Left alone, Pollyanna went back to her "picture," as she mentally designated the beautiful view from the window. After a time she touched the sash tentatively. It seemed as if no longer could she endure the stifling heat. To her joy the sash moved under her fingers. The next moment the window was wide open, and Pollyanna was leaning far out, drinking in the fresh, sweet air.

She ran then to the other window. That, too, soon flew up under her eager hands. A big fly swept past her nose, and buzzed noisily about the room. Then another came, and another; but Pollyanna paid no heed. Pollyanna had made a wonderful discovery--against this window a huge tree flung great branches. To Pollyanna they looked like arms outstretched, inviting her. Suddenly she laughed aloud.

"I believe I can do it," she chuckled. The next moment she had climbed nimbly to the window ledge. From there it was an easy matter to step to the nearest tree-branch. Then, clinging like a monkey, she swung herself from limb to limb until the lowest branch was reached. The drop to the ground was--even for Pollyanna, who was used to climbing trees--a little fearsome. She took it, however, with bated breath, swinging from her strong little arms, and landing on all fours in the soft grass. Then she picked herself up and looked eagerly about her.

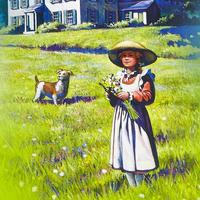

She was at the back of the house. Before her lay a garden in which a bent old man was working. Beyond the garden a little path through an open field led up a steep hill, at the top of which a lone pine tree stood on guard beside the huge rock. To Pollyanna, at the moment, there seemed to be just one place in the world worth being in--the top of that big rock.

With a run and a skilful turn, Pollyanna skipped by the bent old man, threaded her way between the orderly rows of green growing things, and--a little out of breath--reached the path that ran through the open field. Then, determinedly, she began to climb. Already, however, she was thinking what a long, long way off that rock must be, when back at the window it had looked so near!

Fifteen minutes later the great clock in the hallway of the Harrington homestead struck six. At precisely the last stroke Nancy sounded the bell for supper.

One, two, three minutes passed. Miss Polly frowned and tapped the floor with her slipper. A little jerkily she rose to her feet, went into the hall, and looked up-stairs, plainly impatient. For a minute she listened intently; then she turned and swept into the dining room.

"Nancy," she said with decision, as soon as the little serving-maid appeared; "my niece is late. No, you need not call her," she added severely, as Nancy made a move toward the hall door. "I told her what time supper was, and now she will have to suffer the consequences. She may as well begin at once to learn to be punctual. When she comes down she may have bread and milk in the kitchen." "Yes, ma'am." It was well, perhaps, that Miss Polly did not happen to be looking at Nancy's face just then. At the earliest possible moment after supper, Nancy crept up the back stairs and thence to the attic room.

"Bread and milk, indeed!--and when the poor lamb hain't only just cried herself to sleep," she was muttering fiercely, as she softly pushed open the door. The next moment she gave a frightened cry. "Where are you? Where've you gone? Where have you gone?" she panted, looking in the closet, under the bed, and even in the trunk and down the water pitcher. Then she flew down-stairs and out to Old Tom in the garden.

"Mr. Tom, Mr. Tom, that blessed child's gone," she wailed. "She's vanished right up into Heaven where she come from, poor lamb--and me told ter give her bread and milk in the kitchen--her what's eatin' angel food this minute, I'll warrant, I'll warrant!" The old man straightened up.

"Gone? Heaven?" he repeated stupidly, unconsciously sweeping the brilliant sunset sky with his gaze. He stopped, stared a moment intently, then turned with a slow grin. "Well, Nancy, it do look like as if she'd tried ter get as nigh Heaven as she could, and that's a fact," he agreed, pointing with a crooked finger to where, sharply outlined against the reddening sky, a slender, wind-blown figure was poised on top of a huge rock. "Well, she ain't goin' ter Heaven that way ter-night--not if I has my say," declared Nancy, doggedly. "If the mistress asks, tell her I ain't furgettin' the dishes, but I gone on a stroll," she flung back over her shoulder, as she sped toward the path that led through the open field.