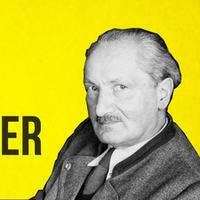

PHILOSOPHY – Martin Heidegger.

PHILOSOPHIE - Martin Heidegger.

ΦΙΛΟΣΟΦΙΑ - Martin Heidegger.

PHILOSOPHY – Martin Heidegger.

FILOSOFÍA - Martin Heidegger.

PHILOSOPHIE - Martin Heidegger.

FILOSOFIA - Martin Heidegger.

PHILOSOPHY - Martin Heidegger.

철학 - 마틴 하이데거.

FILOZOFIA - Martin Heidegger.

FILOSOFIA - Martin Heidegger.

ФИЛОСОФИЯ - Мартин Хайдеггер.

FELSEFE - Martin Heidegger.

ФІЛОСОФІЯ - Мартін Гайдеґґер.

哲学——马丁·海德格尔。

哲學——馬丁·海德格爾。

Martin Heidegger is without doubt the most incomprehensible German philosopher that ever lived.

Martin Heidegger tidak diragukan lagi adalah filsuf Jerman yang paling sulit dipahami yang pernah hidup.

Martin Heidegger é, sem dúvida, o filósofo alemão mais incompreensível que alguma vez existiu.

Martin Heidegger şüphesiz gelmiş geçmiş en anlaşılmaz Alman filozoftur.

Nothing quite rivals the prose in his masterpiece Being and Time, which is filled with complex compound German words like ‘Seinsvergessenheit' ‘Bodenständigkeit' and ‘Wesensverfassung'.

Nada rivaliza con la prosa de su obra maestra Ser y tiempo, repleta de complejas palabras alemanas compuestas como "Seinsvergessenheit", "Bodenständigkeit" y "Wesensverfassung".

Tidak ada yang bisa menyaingi prosa dalam karya besarnya Being and Time, yang dipenuhi dengan kata-kata majemuk bahasa Jerman yang rumit seperti 'Seinsvergessenheit', 'Bodenständigkeit', dan 'Wesensverfassung'.

Nulla è in grado di competere con la prosa del suo capolavoro Essere e tempo, piena di complesse parole tedesche composte come "Seinsvergessenheit", "Bodenständigkeit" e "Wesensverfassung".

Nada rivaliza com a prosa em sua obra-prima Ser e Tempo, que é preenchida com palavras alemãs compostas complexas como 'Seinsvergessenheit' 'Bodenständigkeit' e 'Wesensverfassung'.

Ничто не может сравниться с прозой в его шедевре «Бытие и время», наполненном сложными составными немецкими словами, такими как «Seinsvergessenheit», «Bodenständigkeit» и «Wesensverfassung».

'Seinsvergessenheit' 'Bodenständigkeit' ve 'Wesensverfassung' gibi karmaşık bileşik Almanca sözcüklerle dolu başyapıtı Varlık ve Zaman'daki düzyazıya hiçbir şey rakip olamaz.

Yet beneath the jargon, Heidegger tells us some simple, even at times homespun truths about the meaning of our lives, the sicknesses of our time and the routes to freedom.

Sin embargo, por debajo de la jerga, Heidegger nos dice algunas verdades sencillas, incluso a veces caseras, sobre el sentido de nuestras vidas, las enfermedades de nuestro tiempo y las rutas hacia la libertad.

Namun di balik jargon tersebut, Heidegger memberi tahu kita beberapa kebenaran yang sederhana, bahkan terkadang merupakan kebenaran yang dibuat sendiri tentang makna hidup kita, penyakit di zaman kita, dan jalan menuju kebebasan.

No entanto, sob o jargão, Heidegger nos conta algumas verdades simples, às vezes até caseiras, sobre o significado de nossas vidas, as doenças de nosso tempo e as rotas para a liberdade.

Yine de jargonun altında, Heidegger bize hayatlarımızın anlamı, zamanımızın hastalıkları ve özgürlüğe giden yollar hakkında bazı basit, hatta zaman zaman ev yapımı gerçekler söylüyor.

We should bother with him.

Wir sollten uns um ihn kümmern.

Deberíamos molestarle.

Kita harus repot-repot dengan dia.

Devemos nos preocupar com ele.

He was born, and in many ways remained, a rural provincial German, who loved picking mushrooms, walking in the countryside and going to bed early.

Nació, y en muchos aspectos siguió siendo, un alemán rural de provincias, al que le encantaba recoger setas, pasear por el campo y acostarse temprano.

Dia lahir, dan dalam banyak hal tetap menjadi seorang pedesaan di Jerman, yang suka memetik jamur, berjalan-jalan di pedesaan, dan tidur lebih awal.

Ele nasceu, e de muitas maneiras permaneceu, um alemão rural e provinciano, que adorava colher cogumelos, passear no campo e ir para a cama cedo.

Mantar toplamayı, kırlarda yürümeyi ve erken yatmayı seven taşralı bir Alman olarak doğdu ve birçok yönden öyle kaldı.

He hated television, aeroplanes, pop music and processed food.

Odiaba la televisión, los aviones, la música pop y la comida procesada.

Dia membenci televisi, pesawat terbang, musik pop, dan makanan olahan.

Televizyondan, uçaklardan, pop müzikten ve işlenmiş gıdalardan nefret ederdi.

At one time, he’d been a supporter of Hitler, but saw the error of his ways.

En un tiempo fue partidario de Hitler, pero se dio cuenta de lo equivocado de su postura.

Pada suatu waktu, ia pernah menjadi pendukung Hitler, tetapi melihat kesalahan dari tindakannya.

Bir zamanlar Hitler'in destekçisiydi, ancak yaptığı hatayı gördü.

Much of his life he spent in a hut in the woods, away from modern civilisation.

Sebagian besar hidupnya dihabiskan di sebuah gubuk di dalam hutan, jauh dari peradaban modern.

Hayatının büyük bir bölümünü ormandaki bir kulübede, modern uygarlıktan uzakta geçirdi.

He diagnosed modern humanity as suffering from a number of diseases of the soul.

Diagnosticó que la humanidad moderna padecía una serie de enfermedades del alma.

Ia mendiagnosa manusia modern menderita sejumlah penyakit jiwa.

● Firstly: We have forgotten to notice we’re alive.

● En primer lugar: hemos olvidado darnos cuenta de que estamos vivos.

Pertama: Kita lupa bahwa kita masih hidup.

We know it in theory, of course, but we aren’t day-to-day properly in touch with the sheer mystery of existence, the mystery of what Heidegger called ‘das Sein' or in English, 'Being'.

Lo sabemos en teoría, por supuesto, pero no estamos día a día en contacto con el misterio de la existencia, el misterio de lo que Heidegger llamó "das Sein" o, en español, "el Ser".

Kita mengetahuinya secara teori, tentu saja, tetapi kita tidak setiap hari berhubungan dengan misteri eksistensi, misteri dari apa yang disebut Heidegger sebagai 'das Sein' atau dalam bahasa Inggris, 'Being'.

Elbette bunu teorik olarak biliyoruz, ancak varoluşun katıksız gizemiyle, Heidegger'in 'das Sein' ya da İngilizcede 'Varlık' dediği şeyin gizemiyle her gün doğru dürüst temas halinde değiliz.

It’s only at a few odd moments, perhaps late at night, or when we’re ill and have been alone all day, or are on a walk through the countryside, that we come up against the uncanny strangeness of everything: why things exist as they do, why we are here rather than there, why the world is like it is.

Sólo en algunos momentos extraños, quizá a altas horas de la noche, o cuando estamos enfermos y llevamos todo el día solos, o de paseo por el campo, nos topamos con la extraña extrañeza de todo: por qué las cosas existen como existen, por qué estamos aquí y no allí, por qué el mundo es como es.

Hanya pada saat-saat tertentu, mungkin larut malam, atau saat kita sakit dan sendirian sepanjang hari, atau saat berjalan-jalan di pedesaan, kita akan menemukan keanehan yang luar biasa dari segala sesuatu: mengapa segala sesuatu ada sebagaimana adanya, mengapa kita ada di sini dan bukannya di sana, mengapa dunia ini seperti ini.

What we’re running away from is a confrontation with the opposite of Being, what Heidegger called: ‘das Nichts' (The Nothing).

De lo que estamos huyendo es de una confrontación con lo opuesto al Ser, lo que Heidegger llamó: 'das Nichts' (La Nada).

Apa yang kita hindari adalah konfrontasi dengan kebalikan dari Being, apa yang disebut Heidegger sebagai 'das Nichts' (Ketiadaan).

● The second problems is we have forgotten that all Being is connected.

● El segundo problema es que hemos olvidado que todo Ser está conectado.

Masalah kedua adalah kita telah lupa bahwa semua makhluk saling terhubung.

Most of the time, our jobs and daily routines make us egoistic and focused.

La mayoría de las veces, nuestros trabajos y rutinas diarias nos vuelven egoístas y centrados.

Seringkali, pekerjaan dan rutinitas harian kita membuat kita menjadi egois dan tidak fokus.

We treat others and nature as means and not as ends.

Tratamos a los demás y a la naturaleza como medios y no como fines.

Kami memperlakukan orang lain dan alam sebagai sarana, bukan tujuan.

But occasionally (and again walks in the country are particularly conducive to this realisation), we may step outside our narrow orbit - and take a more expansive view.

Pero de vez en cuando (y los paseos por el campo son especialmente propicios para ello), podemos salir de nuestra estrecha órbita y tener una visión más amplia.

Tetapi kadang-kadang (dan sekali lagi berjalan-jalan di pedesaan sangat kondusif untuk mewujudkan hal ini), kita dapat melangkah keluar dari orbit sempit kita - dan mengambil pandangan yang lebih luas.

We may sense what Heidegger termed 'the Unity of Being', noticing for example that we, and that ladybird on the bark, and that rock, and that cloud over there are all in existence right now and are fundamentally united by the basic fact of our common Being.

Podemos sentir lo que Heidegger denominó "la Unidad del Ser", al darnos cuenta, por ejemplo, de que nosotros, y esa mariquita de la corteza, y esa roca, y esa nube de ahí, todos existimos ahora mismo y estamos fundamentalmente unidos por el hecho básico de nuestro Ser común.

Kita dapat merasakan apa yang disebut Heidegger sebagai 'Kesatuan Wujud', memperhatikan misalnya bahwa kita, dan kepik di kulit kayu itu, dan batu itu, dan awan di atas sana, semuanya ada saat ini dan pada dasarnya disatukan oleh fakta dasar dari keberadaan kita bersama.

Heidegger values these moments immensely - and wants us to use them as the springboard to a deeper form of generosity, an overcoming of alienation and egoism and a more profound appreciation of the brief time that remains to us before ‘das Nichts' claims us in turn.

Heidegger valora inmensamente estos momentos y quiere que los utilicemos como trampolín hacia una forma más profunda de generosidad, una superación de la alienación y el egoísmo y una apreciación más profunda del breve tiempo que nos queda antes de que "das Nichts" nos reclame a su vez.

Heidegger sangat menghargai momen-momen ini - dan ingin kita menggunakannya sebagai batu loncatan menuju bentuk kemurahan hati yang lebih dalam, mengatasi keterasingan dan egoisme, serta apresiasi yang lebih mendalam terhadap waktu singkat yang tersisa bagi kita sebelum 'das Nichts' mengambil alih kita.

● The third problem is we forget to be free and to live for ourselves

Masalah ketiga adalah kita lupa untuk bebas dan hidup untuk diri kita sendiri

Much about us isn’t of course very free.

Mucho de nosotros no es, por supuesto, muy libre.

We are - in Heidegger’s unusual formulation - ‘thrown into the world' at the start of our lives: thrown into a particular and narrow social milieu, surrounded by rigid attitudes, archaic prejudices and practical necessities not of our own making.

Al comienzo de nuestra vida, según la inusual formulación de Heidegger, somos "arrojados al mundo": arrojados a un medio social particular y estrecho, rodeados de actitudes rígidas, prejuicios arcaicos y necesidades prácticas que no son de nuestra propia cosecha.

The philosopher wants to help us to overcome this ‘Thrownness' (‘Geworfenheit' as he puts it in german) by understanding it.

El filósofo quiere ayudarnos a superar este "arrojo" ("Geworfenheit", como él lo llama en alemán) comprendiéndolo.

We need to grasp our psychological, social and professional provincialism - and then rise above it to a more universal perspective.

Tenemos que darnos cuenta de nuestro provincianismo psicológico, social y profesional, y elevarnos por encima de él hacia una perspectiva más universal.

In so doing, we’ll make the classic Heideggerian journey away from ‘Uneigentlichkeit' to ‘Eigentlichkeit' (from Inauthenticity to Authenticity).

Al hacerlo, realizaremos el clásico viaje heideggeriano de la "Uneigentlichkeit" a la "Eigentlichkeit" (de la inautenticidad a la autenticidad).

We will, in essence, start to live for ourselves.

En esencia, empezaremos a vivir para nosotros mismos.

And yet most of the time, for Heidegger, we fail dismally at this task.

Y, sin embargo, la mayoría de las veces, para Heidegger, fracasamos estrepitosamente en esta tarea.

We merely surrender to a socialised, superficial mode of being he called ‘they-self' (as opposed to ‘our-selves').

Simplemente nos rendimos a un modo de ser socializado y superficial que él llamó "ellos-mismos" (en oposición a "nuestros-mismos").

We follow The Chatter (‘das Gerede'), which we hear about in the newspapers, on TV and in the large cities Heidegger hated to spend time in.

Seguimos La Charla ('das Gerede'), de la que oímos hablar en los periódicos, en la televisión y en las grandes ciudades en las que Heidegger odiaba pasar el tiempo.

What will help us to pull away from the ‘they-self' is an appropriately intense focus on our own upcoming death.

Lo que nos ayudará a alejarnos del "ellos-mismos" es una concentración adecuadamente intensa en nuestra propia muerte próxima.

It’s only when we realise that other people cannot save us from ‘das Nichts' that we’re likely to stop living for them; to stop worrying so much about what others think, and to cease giving up the lion’s share of our lives and energies to impress people who never really liked us in the first place.

Sólo cuando nos demos cuenta de que los demás no pueden salvarnos de "das Nichts" dejaremos de vivir para ellos, dejaremos de preocuparnos tanto por lo que piensen los demás y dejaremos de dedicar la mayor parte de nuestras vidas y energías a impresionar a personas a las que nunca les hemos gustado.

When in a lecture, in 1961, Heidegger was asked how we should better lead our lives, he replied tersely that we should simply aim to spend more time ‘in graveyards'.

Cuando en una conferencia, en 1961, se le preguntó a Heidegger cómo deberíamos llevar mejor nuestras vidas, respondió escuetamente que simplemente deberíamos proponernos pasar más tiempo "en los cementerios".

It would be lying to say that Heidegger’s meaning and moral is ever very clear.

Sería mentir decir que el sentido y la moraleja de Heidegger nunca están muy claros.

Nevertheless, what he tells us is intermittently fascinating, wise and surprisingly useful.

Despite the extraordinary words and language, in a sense, we know a lot of it already.

A pesar de lo extraordinario de las palabras y el lenguaje, en cierto sentido, ya sabemos mucho.

We merely need reminding and emboldening to take it seriously, which the odd prose style helps us to do.

Sólo necesitamos que nos lo recuerden y nos animen a tomárnoslo en serio, a lo que nos ayuda el extraño estilo de la prosa.

We know in our hearts that it is time to overcome our ‘Geworfenheit', that we should become more conscious of ‘das Nichts' day-to-day, and that we owe it to ourselves to escape the clutches of ‘das Gerede' for the sake of ‘Eigentlichkeit' - with a little help from that graveyard.

Sabemos de corazón que ha llegado el momento de superar nuestra "Geworfenheit", que debemos ser más conscientes de "das Nichts" día a día, y que nos debemos a nosotros mismos escapar de las garras de "das Gerede" en aras de la "Eigentlichkeit", con un poco de ayuda de ese cementerio.