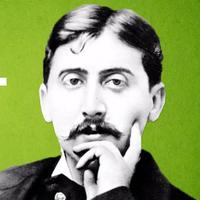

Marcel Proust. LITERATURE. Part 1/2.

مارسيل بروست. المؤلفات. الجزء 1/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATUR. Teil 1/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATURA. Parte 1/2.

Marcel Proust. LITTÉRATURE. Partie 1/2.

Marcel Proust. LETTERATURA. Parte 1/2.

マルセル・プルーストLITERATUREパート1/2

Marcelis Prustas. LITERATŪRA. 1/2 dalis.

Marcel Proust. LITERATURA. Część 1/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATURA. Parte 1/2.

Марсель Пруст. ЛИТЕРАТУРА. Часть 1/2.

Marcel Proust. EDEBİYAT. Bölüm 1/2.

Марсель Пруст. ЛІТЕРАТУРА. Частина 1/2.

马塞尔·普鲁斯特。文学。第 1/2 部分。

馬塞爾·普魯斯特。文學。第 1/2 部分。

[:]placeholder="Type the lesson text here...">Marcel Proust was an early 20th-century French writer responsible for what is officially the longest novel in the world: “À la recherche du temps perdu” [1] – which has 1.2 million words in it (which has 1,267,069 words in it); double those in War and Peace.

[:] placeholder = "اكتب نص الدرس هنا ..."> كان مارسيل بروست كاتبًا فرنسيًا من أوائل القرن العشرين مسئولًا عن أطول رواية في العالم رسميًا: "À la recherche du temps perdu" [1] - التي تحتوي على 1.2 مليون كلمة (بها 1267.069 كلمة) ؛ ضعف هؤلاء في الحرب والسلام.

[:]placeholder="Geben Sie den Lektionstext hier ein...">Marcel Proust war ein französischer Schriftsteller des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts, der für den offiziell längsten Roman der Welt verantwortlich ist: "À la recherche du temps perdu" [1] - mit 1,2 Millionen Wörtern (mit 1.267.069 Wörtern); doppelt so viele wie in Krieg und Frieden.

[:]placeholder="ここにレッスンテキストを入力してください...">マルセル・プルーストは20世紀初頭のフランスの作家で、公式には世界で最も長い小説とされている「À la recherche du temps perdu」 [1] を執筆しました。この小説には120万語(126万7069語:「戦争と平和」の2倍)含まれています。

[:]placeholder="Введіть текст уроку тут...">Марсель Пруст - французький письменник початку 20-го століття, автор офіційно найдовшого роману у світі: "У пошуках втраченого часу" [1], який налічує 1,2 мільйона слів (1 267 069 слів); удвічі більше, ніж у "Війні і мирі".

The book was published in French in seven volumes over 14 years, and was immediately recognised to be a masterpiece, ranked by many as the greatest novel of the century, or simply of all time.

نُشر الكتاب باللغة الفرنسية في سبعة مجلدات على مدار 14 عامًا ، وتم الاعتراف به فورًا على أنه تحفة فنية ، صنفها الكثيرون على أنه أعظم رواية في القرن ، أو ببساطة في كل العصور.

Das Buch wurde auf Französisch in sieben Bänden innerhalb von 14 Jahren veröffentlicht und wurde sofort als Meisterwerk anerkannt, das von vielen als der größte Roman des Jahrhunderts oder einfach aller Zeiten bezeichnet wurde.

Книга була опублікована французькою мовою у семи томах протягом 14 років і одразу ж була визнана шедевром, багато хто називає її найбільшим романом століття, або просто всіх часів і народів.

What makes it so special is that it isn't just a novel in the straight narrative sense.ass="mceAudioTime">[:] It is a work that intersperses genius-level descriptions of people and places with a whole philosophy of life.

ما يجعله مميزًا هو أنه ليس مجرد رواية بالمعنى السردي المباشر.

Що робить його особливим, так це те, що це не просто роман у прямому наративному сенсі.ass="mceAudioTime">[:] Це твір, в якому геніальні описи людей і місць перемежовуються з цілою філософією життя.

[:] The clue is in the title:

[:] الدليل موجود في العنوان:

[Der Hinweis ist im Titel enthalten:

<p placeholder="Type the lesson text here...">“In Search of Lost Time.” [“À la recherche du temps perdu”]

<p placeholder="Geben Sie den Lektionstext hier ein...">"Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit". ["À la recherche du temps perdu"]

The book tells the story of one man – a thinly disguised version of Proust himself – in his ongoing (developing) search for the meaning and purpose of life.

يحكي الكتاب قصة رجل واحد - نسخة مقنعة إلى حد ما لبروست نفسه - في بحثه المستمر (المتطور) عن معنى وهدف الحياة.

Das Buch erzählt die Geschichte eines Mannes - einer leicht verkleideten Version von Proust selbst - auf seiner (sich entwickelnden) Suche nach dem Sinn und Zweck des Lebens.

It recounts his quest to stop wasting time and to start to appreciate existence.

يروي سعيه للتوقف عن إضاعة الوقت والبدء في تقدير الوجود.

Er erzählt von seiner Suche, keine Zeit mehr zu verschwenden und die Existenz zu schätzen.

[:]eholder="Type the lesson text here...">Marcel Proust wanted his book to help us, above all.>[:] His father, Adrien Proust, had been one of the great doctors of his age, responsible for wiping out cholera in France.

[:] eholder = "اكتب نص الدرس هنا ..."> أراد مارسيل بروست أن يساعدنا كتابه ، قبل كل شيء.> [:] كان والده ، أدريان بروست ، أحد أعظم الأطباء في عصره ، وكان مسؤولاً للقضاء على الكوليرا في فرنسا.

[:]eholder="Geben Sie hier den Lektionstext ein...">Marcel Proust wollte mit seinem Buch vor allem uns helfen.>[:] Sein Vater, Adrien Proust, war einer der großen Ärzte seiner Zeit, der für die Ausrottung der Cholera in Frankreich verantwortlich war.

Towards the end of his life, his frail, indolent son Marcel, who had lived on his inheritance and had disappointed his family by never taking up a regular job, told his housekeeper Celeste: ‘If only I could do for humanity as much good with my books as my father did with his work.

قرب نهاية حياته ، أخبر ابنه الضعيف ، مارسيل ، الذي عاش على ميراثه وخيب أمل عائلته بعدم توليه وظيفة منتظمة ، لمدبرة منزله سيليست: كتبي كما فعل والدي مع عمله.

Gegen Ende seines Lebens sagte sein gebrechlicher, träger Sohn Marcel, der von seinem Erbe lebte und seine Familie enttäuschte, weil er nie einer geregelten Arbeit nachging, zu seiner Haushälterin Celeste: "Wenn ich doch nur mit meinen Büchern so viel Gutes für die Menschheit tun könnte, wie mein Vater es mit seiner Arbeit tat.

彼の人生の終わりに向かって、彼の虚弱で怠惰な息子のマルセルは、彼の遺産で生活し、通常の仕事に就かなかったために家族を失望させました.私の父が彼の仕事でしたように私の本。

'[2] The important news is that he amply succeeded.

[:]der="Type the lesson text here...">Proust's novel charts the narrator's systematic exploration of three possible sources of the meaning of life.]

[:]der="Geben Sie hier den Lektionstext ein...">Prousts Roman beschreibt die systematische Erkundung dreier möglicher Quellen für den Sinn des Lebens durch den Erzähler].

The first is: SOCIAL SUCCESS.ss="mceAudioTime">[:] Proust was born into a comfortable bourgeois household; but from his teens, he began to think that the meaning of life might lie in joining high society, which in his day meant, the world of aristocrats, of dukes, duchesses and princes.

Die erste ist: SOCIAL SUCCESS.ss="mceAudioTime">[:] Proust wurde in ein bequemes bürgerliches Haus hineingeboren; aber schon als Jugendlicher begann er zu denken, dass der Sinn des Lebens darin liegen könnte, sich der High Society anzuschließen, was zu seiner Zeit die Welt der Aristokraten, der Herzöge, Herzoginnen und Prinzen bedeutete.

[:] But if you convert this to the present day, that would mean celebrities.

[Aber wenn man das auf die heutige Zeit überträgt, würde das bedeuten, dass es sich um Prominente handelt.

For years, the narrator devotes his energies to working his way up the social hierarchy; and because he's charming and erudite, he eventually becomes friends with lynchpins of Parisian high society, the Duke and Duchesse de Guermantes.

Jahrelang versucht der Erzähler, sich in der gesellschaftlichen Hierarchie nach oben zu arbeiten, und weil er charmant und gelehrt ist, freundet er sich schließlich mit den Dreh- und Angelpunkten der Pariser High Society an, dem Herzog und der Herzogin de Guermantes.

But a troubling realisation soon dawns on him.

Doch schon bald dämmert ihm eine beunruhigende Erkenntnis.

These people are not the extraordinary paragons he imagined they would be.

The Duc's conversation is boring and crass.

The Duchesse, though well mannered, is cruel and vain.

Die Duchesse ist zwar gut erzogen, aber grausam und eitel.

[:]lder="Type the lesson text here...">Marcel tires of them and their circle.>[:] He realises that virtues and vices are scattered throughout the population without regard to income or renown.

[:]lder="Geben Sie hier den Lektionstext ein...">Marcel wird ihrer und ihres Kreises überdrüssig.>[:] Er stellt fest, dass Tugenden und Laster in der Bevölkerung verstreut sind, ohne Rücksicht auf Einkommen oder Ansehen.

He grows free to devote himself to a wider range of people.

Er wird frei, sich einem größeren Kreis von Menschen zu widmen.

Though Proust spends many pages lampooning social snobbery, it's in a spirit of understanding and underlying sympathy.

Obwohl sich Proust auf vielen Seiten über den gesellschaftlichen Snobismus lustig macht, geschieht dies aus einem Geist des Verständnisses und der unterschwelligen Sympathie.

It is a highly natural error, especially when one is young, to suspect that there might be a class of superior people somewhere out in the world and that our lives might be dull principally because we don't have the right contacts.

Es ist ein ganz natürlicher Irrtum, vor allem wenn man jung ist, zu vermuten, dass es irgendwo auf der Welt eine Klasse von überlegenen Menschen gibt und dass unser Leben vor allem deshalb langweilig ist, weil wir nicht die richtigen Kontakte haben.

But Proust's novel offers definitive reassurance: life is not going on elsewhere.

Doch Prousts Roman bietet die endgültige Gewissheit: Das Leben spielt sich nicht anderswo ab.

There is no party where the perfect people are.

The second thing that Proust's narrator investigates in his quest for the meaning of life is: LOVE.

In the second volume of the novel, the narrator goes off to the seaside with his grandmother, to the vogueish resort of Cabourg (the Barbados of the times).

Im zweiten Band des Romans fährt der Erzähler mit seiner Großmutter ans Meer, in den mondänen Badeort Cabourg (das Barbados der damaligen Zeit).

There he develops an overwhelming crush on a beautiful teenage girl called Albertine.

Dort verknallt er sich in ein wunderschönes Teenager-Mädchen namens Albertine.

She has short hair, a boyish smile and a charming, casual way of speaking.

Sie hat kurze Haare, ein jungenhaftes Lächeln und eine charmante, lockere Art zu sprechen.

For about 300 pages, all the narrator can think about is Albertine.

The meaning of life surely must lie in loving her.

Der Sinn des Lebens muss wohl darin liegen, sie zu lieben.

But with time, here too, there's disappointment.

The moment comes when the narrator is finally allowed to kiss Albertine:

“Man, a creature clearly less rudimentary than the sea-urchin or even the whale, nevertheless lacks a certain number of essential organs, and particularly possesses none that will serve for kissing.

"Der Mensch, ein Geschöpf, das deutlich weniger rudimentär ist als der Seeigel oder sogar der Wal, verfügt dennoch über eine Reihe wesentlicher Organe und insbesondere über keines, das zum Küssen geeignet ist.

For this absent organ he substitutes his lips, and perhaps he thereby achieves a result slightly more satisfying than caressing his beloved with a horny tusk…”[3]

Dieses fehlende Organ ersetzt er durch seine Lippen, und vielleicht erreicht er damit ein etwas befriedigenderes Ergebnis als die Liebkosung seiner Geliebten mit einem geilen Stoßzahn..."[3]

The ultimate promise of love, in Proust's eyes, is that we can stop being alone and properly fuse our life with that of another person who will understand every part of us.

Für Proust besteht das ultimative Versprechen der Liebe darin, dass wir aufhören können, allein zu sein, und unser Leben mit dem einer anderen Person verschmelzen können, die jeden Teil von uns verstehen wird.

But the novel comes to darker conclusions: no one can fully understand anyone.

Doch der Roman kommt zu einem dunkleren Schluss: Niemand kann jemanden vollständig verstehen.

Loneliness is endemic.

Die Einsamkeit ist endemisch.

We're awkwardly lonely pilgrims, trying to give each tusk-kisses in the dark.

Wir sind unbeholfene, einsame Pilger, die versuchen, sich im Dunkeln gegenseitig Küsschen zu geben.