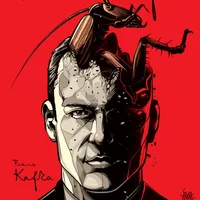

Franz Kafka - Metaphomorsisis chapter 3

III Gregor's serious wound, from which he suffered

for over a month, since no one ventured to remove the apple it remained in his flesh

as a visible reminder, seemed by itself to have reminded the father that, in spite of

his present unhappy and hateful appearance, Gregor was a member of the family, something

one should not treat as an enemy, and that it was, on the contrary, a requirement of

family duty to suppress one's aversion and to endure. Nothing else, just endure. And

if through his wound Gregor had not apparently lost for good his ability to move, and for

the time being needed many, many minutes to crawl across the room, like an aged invalid,

as far as creeping up high was concerned, that was unimaginable, nevertheless, for this

worsening of his condition, in his opinion, it did get completely satisfactory compensation,

because every day towards evening the door to the living-room, which he was in the habit

of keeping a sharp eye on, even one or two hours beforehand, was opened, so that he,

lying down in the darkness of his room, invisible from the living-room, could see the entire

family at the illuminated table, and listen to their conversation, to a certain extent

with their common permission, a situation quite different from what had happened before.

Of course it was no longer the animated social interaction of former times, which Gregor

in small hotel rooms had always thought about with a certain longing, when, tired out, he

had had to throw himself into the damp bedclothes.

For the most part what went on now was very quiet.

After the evening meal the father fell asleep quickly in his arm-chair.

The mother and sister talked guardedly to each other in the stillness.

Bent far over the mother sewed fine undergarments for a fashion-shop.

The sister, who had taken on a job as a sales-girl, in the evening studied stenography and French,

so as perhaps later to obtain a better position.

Sometimes the father woke up, and, as if he was quite ignorant that he had been asleep,

said to the mother,

"'How long have you been sewing to-day?' and went right back to sleep, while the mother

and the sister smiled tiredly to each other.

With a sort of stubbornness the father refused to take off his servant's uniform even at

home, and while his sleeping-gown hung unused on the coat-hook, the father dozed completely

dressed in his place, as if he was always ready for his responsibility, and even here

was waiting for the voice of his superior.

As a result, in spite of all the care of the mother and sister, his uniform, which even

at the start was not new, grew dirty, and Gregor looked, often for the entire evening,

at his clothing, with stains all over it, and with its gold buttons always polished,

in which the old man, although very uncomfortable, slept peacefully nonetheless.

As soon as the clock struck ten, the mother tried gently encouraging the father to wake

up, and then persuading him to go to bed, on the ground that he couldn't get a proper

sleep here, and that the father, who had to report for service at six o'clock, really

needed a good sleep.

But in his stubbornness, which had gripped him since he had become a servant, he insisted

always on staying even longer by the table, although he regularly fell asleep, and then

could only be prevailed upon with the greatest difficulty to trade his chair for the bed.

No matter how much the mother and sister might at that point work on him with small admonitions,

for a quarter of an hour he would remain shaking his head slowly, his eyes closed, without

standing up.

The mother would pull him by the sleeve and speak flattering words into his ear.

The sister would leave her work to help her mother, but that would not have the desired

effect on the father.

He would settle himself even more deeply in his arm-chair.

Only when the two women grabbed him under the armpits, would he throw his eyes open,

look back and forth at the mother and sister, and habitually say,

This is a life!

This is the peace and quiet of my old age!

And propped up by both women, he would heave himself up elaborately, as if for him it was

the greatest trouble, allow himself to be led to the door by the women, wave them away

there, and proceed on his own from there, while the mother quickly threw down her sewing

implements and the sister her pen, in order to run after the father and help him some

more.

In this overworked and exhausted family, who had time to worry any longer about Gregor

more than was absolutely necessary?

The household was constantly getting smaller.

The servant-girl was now let go.

A huge bony cleaning-woman, with white hair flying all over her head, came in the morning

and evening to do the heaviest work.

The mother took care of everything else, in addition to her considerable sewing-work.

It even happened that various pieces of family jewellery, which previously the mother and

sister had been overjoyed to wear on social and festive occasions, were sold, as Gregor

found out in the evening from the general discussion of the prices they had fetched.

But the greatest complaint was always that they could not leave this apartment, which

was too big for their present means, since it was impossible to imagine how Gregor might

be moved.

But Gregor finally recognized, but Gregor fully recognized, that it was not just consideration

for him which was preventing a move, for he could have been transported easily in a suitable

box with a few air-holes.

The main thing holding the family back from a change in living-quarters was far more their

complete hopelessness, and the idea that they had been struck by a misfortune like no one

else in their entire circle of relatives and acquaintances.

But the world demands of poor people they now carried out to an extreme degree.

The father brought breakfast to the petty officials at the bank, the mother sacrificed

herself for the undergarments of strangers, the sister behind her desk was at the beck

and call of customers, but the family's energies did not extend any further.

And the wound in his back began to pain Gregor all over again, when now mother and sister,

after they had escorted the father to bed, came back, let their work lie, moved closer

together, and sat cheek to cheek, and when his mother would now say, pointing to Gregor's

room, "'Close the door, Greta,' and when Gregor was again in the darkness, while close

by the women mingled their tears, or, quite dry-eyed, stared at the table.

Gregor spent his nights and days with hardly any sleep.

Sometimes he thought that the next time the door opened he would take over the family

arrangements just as he had earlier.

In his imagination appeared again, after a long time, his employer and supervisor and

the apprentices, the excessively spineless custodian, two or three friends from other

businesses, a chambermaid from a hotel in the provinces, a loving fleeting memory, a

female cashier from a hat-shop, whom he had seriously but too slowly courted.

They all appeared mixed in with strangers or people he had already forgotten, but instead

of helping him and his family, they were all unapproachable, and he was happy to see them

disappear.

But then he was in no mood to worry about his family.

He was filled with sheer anger over the wretched care he was getting, even though he couldn't

imagine anything which he might have an appetite for.

Still, he made plans about how he could take from the larder what he at all account deserved,

even if he wasn't hungry.

Without thinking any more about how they might be able to give Gregor special pleasure, the

sister now kicked some food or other very quickly into his room in the morning or at

noon before she ran off to her shop, and in the evening, quite indifferent to whether

the food had perhaps only been tasted, or what happened most frequently, remained entirely

undisturbed, she whisked it out with one sweep of her broom.

The task of cleaning his room, which she now always carried out in the evening, could not

be done any more quickly.

Streaks of dirt ran along the walls, here and there lay tangles of dust and garbage.

At first, when his sister arrived, Gregor positioned himself in a particularly filthy

corner, in order with this posture to make something of a protest, but he could have

well stayed there for weeks without his sister's changing her ways.

In fact, she perceived the dirt as much as he did, but she had decided just to let it

stay.

In this business, with a touchiness which was quite new to her, and which had generally

taken over the entire family, she kept watch to see that the cleaning of Gregor's room

remained reserved for her.

Once his mother had undertaken a major cleaning of Gregor's room, which she had only completed

using a few buckets of water, but the extensive dampness made Gregor sick, and he lay supine,

embittered, and immobile on the couch.

However the mother's punishment was not delayed for long, for in the evening the sister had

hardly observed the change in Gregor's room, before she ran into the living-room mightily

offended, and in spite of her mother's hand lifted high in entreaty, broke out in a fit

of crying.

Her parents—her father had, of course, woken up with a start in his arm-chair—at first

looked at her astonished and helpless, until they started to get agitated.

Turning to his right, the father heaped reproaches on the mother that she was not to take over

the cleaning of Gregor's room from the sister, and turning to his left, he shouted at the

sister that she would no longer be allowed to clean Gregor's room ever again.

While the mother tried to pull the father, beside himself in his excitement, into the

bedroom.

The sister, shaken by her crying fits, pounded on the table with her tiny fists, and Gregor

hissed at all this, angry that no one thought about shutting the door and sparing him the

sight of this commotion.

But even when the sister, exhausted from her daily work, had grown tired of caring for

Gregor as she had before, even then the mother did not have to come at all on her behalf,

and Gregor did not have to be neglected, for now the cleaning-woman was there.

This old widow, who in her long life must have managed to survive the worst with the

help of her bony frame, had no real horror of Gregor.

Without being in the least curious, she had once by chance opened Gregor's door.

At the sight of Gregor, who, totally surprised, began to scamper here and there, although

no one was chasing him, she remained standing with her hands folded across her stomach,

staring at him.

Since then she did not fail to open the door furtively a little every morning and evening

to look in on Gregor.

At first she also called him to her with words which she presumably thought were friendly,

like,

"'Come here for a bit, old dung-beetle,' or,

"'Hey, look at the old dung-beetle!'

Addressed in such a manner, Gregor answered nothing, but remained motionless in his place,

as if the door had not been opened at all.

If only, instead of allowing this cleaning-woman to disturb him uselessly whenever she felt

like it, they had given her orders to clean up his room every day.

One day in the early morning, a hard downpour, perhaps already a sign of the coming spring,

struck the window-panes, when the cleaning-woman started up once again with her usual conversation,

Gregor was so bitter that he turned towards her, as if for an attack, although slowly

and weakly.

But instead of being afraid of him, the cleaning-woman merely lifted up a chair standing close by

the door, and as she stood there with her mouth wide open, her intention was clear.

She would close her mouth only when the chair in her hand had been thrown down on Gregor's

back.

"'This goes no further, all right?' she asked, as Gregor turned himself round again,

and she placed the chair calmly back in the corner.

Gregor ate hardly anything any more.

Only when he chanced to move past the food which had been prepared, did he, as a game,

take a bit into his mouth, hold it there for hours, and generally spit it out again.

At first he thought it might be his sadness over the condition of his room which kept

him from eating, but he very soon became reconciled to the alterations in his room.

People had grown accustomed to put into storage in his room things which they couldn't put

anywhere else, and at this point there were many such things, now that they had rented

one room of the apartment to three lodgers.

These solemn gentlemen, all three had full beards, as Gregor once found out through a

crack in the door, were meticulously intent on tidiness, not only in their own room, but,

since they had now rented a room here, in the entire household, and particularly in

the kitchen.

They simply did not tolerate any useless or shoddy stuff.

Moreover, for the most part they had brought with them their own pieces of furniture.

Thus, many items had become superfluous, and those were not really things one could sell

or things people wanted to throw out.

All these items ended up in Gregor's room, even the box of ashes and the garbage-pail

from the kitchen.

The cleaning-woman, always in a hurry, simply flung anything that was momentarily useless

into Gregor's room.

Fortunately, Gregor genuinely saw only the relevant object and the hand which held it.

The cleaning-woman, perhaps, was intending, when time and opportunity allowed, to take

the stuff out again, or to throw everything out all at once, but in fact the things remained

lying there, wherever they had ended up at the first throw, unless Gregor squirmed his

way through the accumulation of junk and moved it.

At first he was forced to do this because otherwise there was no room for him to creep

around, but later he did it with a growing pleasure, although, after such movements,

tired to death and feeling wretched, he didn't budge for hours.

Because the lodgers sometimes also took their evening meal at home in the common living-room,

the door to the living-room stayed shut on many evenings, but Gregor had no trouble at

all going without the open door.

Already on many evenings, when it was open, he had not availed himself of it, but without

the family noticing, was stretched out in the darkest corner of his room.

However, once the cleaning-woman had left the door to the living-room slightly ajar,

and it remained open even when the lodgers came in in the evening and the lights were

put on.

They sat down at the head of the table, where in earlier days the mother, the father, and

Gregor had eaten, unfolded their serviettes, and picked up their knives and forks.

The mother immediately appeared in the door with a dish of meat, and right behind her

the sister with a dish piled high with potatoes.

The food gave off a lot of steam.

The gentleman lodgers bent over the plate set before them, as if they wanted to check

it before eating, and in fact the one who sat in the middle, for the other two he seemed

to serve as the authority, cut off a piece of meat still on the plate, obviously to establish

whether it was sufficiently tender, and whether or not something should be shipped back to

the kitchen.

He was satisfied, and mother and sister, who had looked on in suspense, began to breathe

easily and to smile.

The family itself ate in the kitchen.

In spite of that, before the father went into the kitchen, he came into the room, and with

a single bow, cap in hand, made a tour of the table.

The lodgers rose up collectively, and murmured something in their beards.

Then when they were alone, they ate almost in complete silence.

It seemed odd to Gregor that, out of all the many different sorts of sounds of eating,

what was always audible was their chewing teeth, as if by that Gregor should be shown

that people needed their teeth to eat, and that nothing could be done even with the most

handsome toothless jar-bone.

I really do have an appetite," Gregor said to himself sorrowfully,

but not for these things.

How these lodgers stuff themselves, and I am dying!

On this very evening the violin sounded from the kitchen.

Gregor didn't remember hearing it at all through this period.

The lodgers had already ended their night meal, the middle one had pulled out a newspaper

and had given each of the other two a page, and they were now leaning back, reading and

smoking.

When the violin started playing, they became attentive, got up, and went on tiptoe to the

hall door, at which they remained standing, pressed up against one another.

They must have been audible from the kitchen, because the father called out,

"'Perhaps the gentlemen don't like the playing.

It can be stopped at once.'

"'On the contrary,' stated the lodger in the middle,

"'might the young woman not come into us and play in the room here, where it is really

much more comfortable and cheerful?'

"'Oh, thank you!' cried out the father, as if he were the one playing the violin.

The men stepped back into the room and waited.

Soon the father came with the music-stand, the mother with the sheet-music, and the sister

with the violin.

The sister calmly prepared everything for the recital.

The parents, who had never previously rented a room, and therefore exaggerated their politeness

to the lodgers, dared not sit on their own chairs.

The father leaned against the door, his right hand stuck between two buttons of his buttoned-up

uniform.

The mother, however, accepted a chair offered by one lodger.

Since she left the chair sit where the gentleman had chanced to put it, she sat to one side

in a corner.

The sister began to play.

The father and mother, one on each side, followed attentively the movements of her hands.

Attracted by the playing, Gregor had ventured to advance a little further forward, and his

head was already in the living-room.

He scarcely wondered about the fact that recently he had had so little consideration for the

others.

Earlier this consideration had been something he was proud of, and for that very reason

he would have had at this moment more reason to hide away, because, as a result of the

dust which lay all over his room and flew around with the slightest movement, he was

totally covered in dirt.

On his back and his sides he carted around with him dust, threads, hair, and remnants

of food.

His indifference to everything was much too great for him to lie on his back and scour

himself on the carpet, as he often had done earlier during the day.

In spite of his condition he had no timidity about inching forward a bit on the spotless

floor of the living-room.

In any case, no one paid any attention.

The family was all caught up in the violin-playing.

The lodgers, by contrast, who for the moment had placed themselves, hands in their trouser

pockets, behind the music-stand, much too close to the sister, so that they could all

see the sheet-music—something that must certainly bother the sister—soon drew back

to the window, conversing in low voices with bowed heads, where they then remained, worriedly

observed by the father.

It now seemed really clear that, having assumed they were to hear a beautiful or entertaining

violin recital, they were disappointed, and were allowing their peace and quiet to be

disturbed only out of politeness.

The way in which they all blew the smoke from their cigars out of their noses and mouths,

in particular, led one to conclude that they were very irritated.

And yet his sister was playing so beautifully.

Her face was turned to the side, her gaze followed the score intently and sadly.

Gregor crept forward still a little further, keeping his head close against the floor,

in order to be able to catch her gaze if possible.

Was he an animal that music so captivated him?

For him it was as if the way to the unknown nourishment he craved was revealing itself.

He was determined to press forward right to his sister, to tug at her dress, and to indicate

to her in this way that she might still come with her violin into his room, because here

no one valued the recital as he wanted to value it.

He did not wish to let her go from his room any more, at least not as long as he lived.

This frightening appearance would for the first time become useful for him.

He wanted to be at all the doors of his room simultaneously, and snarl back at the attackers.

However, his sister should not be compelled, but would remain with him voluntarily.

She would sit next to him on the sofa, bend down her ear to him, and he would then confide

in her that he firmly intended to send her to the conservatory, and that, if his misfortune

had not arrived in the interim, he would have declared all this last Christmas.

Had Christmas really already come and gone?

And would have brooked no argument?

After this explanation his sister would break out in tears of emotion, and Gregor would

lift himself up to her armpit and kiss her throat, which she, from the time she started

going to work, had left exposed, without a band or a collar.

Mr. Samsa!" called out the middle lodger to the father, and, without uttering a further

word, pointed his index finger at Gregor, as he was slowly moving forward.

The violin fell silent.

The middle lodger smiled, first shaking his head once at his friends, and then looked

down at Gregor once more.

Rather than driving Gregor back again, the father seemed to consider it of prime importance

to calm down the lodgers, although they were not at all upset, and Gregor seemed to entertain

them more than the violin recital.

The father hurried over to them, and with outstretched arms tried to push them into

their own room, and simultaneously block their view of Gregor with his own body.

At this point they became really somewhat irritated, although one no longer knew whether

that was because of the father's behavior, or because of knowledge they had just acquired

that they had, without knowing it, a neighbor like Gregor.

They demanded explanations from his father, raised their arms to make their points, tugged

agitatedly at their beards, and moved back towards their room quite slowly.

In the meantime, the isolation which had suddenly fallen upon his sister after the sudden breaking

off of the recital, had overwhelmed her.

She had held on to the violin and bow in her limp hands for a little while, and had continued

to look at the sheet music as if she were still playing.

All at once she pulled herself together, placed the instrument in her mother's lap—the mother

was still sitting in her chair having trouble breathing, for her lungs were laboring—and

had run into the next room, which the lodgers, pressured by the father, were already approaching

more rapidly.

One could observe how, under the sister's practiced hands, the sheets and pillows on

the beds were thrown on high and arranged.

Even before the lodgers had reached the room, she was finished fixing the beds, and was

slipping out.

The father seemed so gripped once again with his stubbornness, that he forgot about the

respect which he always owed to his renters.

He pressed on and on, until at the door of the room the middle gentleman stamped loudly

with his foot, and thus brought the father to a standstill.

"'I hereby declare,' the middle lodger said, raising his hand and casting his glance both

on the mother and the sister, that considering the disgraceful conditions prevailing in this

apartment and family—with this he spat decisively on the floor—'I immediately cancel my room.

I will, of course, pay nothing at all for the days which I have lived here.

On the contrary, I shall think about whether or not I will initiate some sort of action

against you—something which, believe me, will be very easy to establish.'

He fell silent, and looked directly in front of him, as if he was waiting for something.

In fact, his two friends immediately joined in with their opinions.

We also gave immediate notice.

At that he seized the door-handle, banged the door shut, and locked it.

The father groped his way tottering to his chair, and let himself fall in it.

It looked as if he was stretching out for his usual evening snooze, but the heavy nodding

of his head, which looked as if it was without support, showed that he was not sleeping at

all.

Gregor had lain motionless the entire time in the spot where the lodges had caught him.

Disappointment with the collapse of his plan, and perhaps also weakness brought on by his

severe hunger, made it impossible for him to move.

He was certainly afraid that a general disaster would break over him at any moment, and he

waited.

He was not even startled when the violin fell from the mother's lap, out from under her

trembling fingers, and gave off a reverberating tone.

"'My dear parents,' said the sister, banging her hand on the table by way of an introduction,

"'things cannot go on any longer in this way.

Maybe if you don't understand that—well, I do—I will not utter my brother's name

in front of this monster, and thus I say only that we must try to get rid of it.

We have tried what is humanly possible to take care of it, and to be patient.

I believe that no one can criticise us in the slightest.'

"'She is right in a thousand ways,' said the father to himself.

The mother, who was still incapable of breathing properly, began to cough numbly with her hand

held up over her mouth, and a manic expression in her eyes.

The sister hurried over to her mother and held her forehead.

The sister's words seemed to have led the father to certain reflections.

He sat upright, played with his uniform hat among the plates, which still lay on the table

from the lodger's evening meal, and looked now and then at the motionless Gregor.

"'We must try to get rid of it,' the sister now said decisively to the father, for the

mother, in her coughing fit, was not listening to anything.

"'It is killing you both.

I see it coming.

When people have to work as hard as we all do, they cannot also tolerate this endless

torment at home.

I just can't go on any more.'

And she broke out into such a crying fit that her tears flowed out down onto her mother's

face.

She wiped them off her mother with mechanical motions of her hands.

"'My child,' said the father sympathetically and with obvious appreciation, "'then what

shall we do?'

The sister only shrugged her shoulders as a sign of the perplexity which, in contrast

to her previous confidence, had come over her while she was crying.

"'If only he understood us,' said the father in a semi-questioning tone.

The sister, in the midst of her sobbing, shook her head energetically as a sign that there

was no point thinking of that.

"'If he only understood us,' repeated the father, and by shutting his eyes he absorbed

the sister's conviction of the impossibility of this point, "'then perhaps some compromise

would be possible with him.

But as it is—'

"'It must be gotten rid of,' cried the sister.

"'That is the only way, father.

You must try to get rid of the idea that this is Gregor.

The fact that we have believed for so long, that is truly our real misfortune.

But how can it be Gregor?

If it were Gregor, he would have long ago realized that a communal life among human

beings is not possible with such an animal, and would have gone away voluntarily.

Then we would not have a brother, but we could go on living and honor his memory.

But this animal plagues us.

It drives away the lodgers, will obviously take over the entire apartment, and leave

us to spend the night in the alley.

Just look, father!' she suddenly cried out.

"'He's already starting up again!'

With a fright which was totally incomprehensible to Gregor, the sister even left the mother,

pushed herself away from her chair, as if she would sooner sacrifice her mother than

remain in Gregor's vicinity, and rushed behind her father, who, excited merely by her behavior,

also stood up and half raised his arms in front of the sister, as though to protect

her.

But Gregor did not have any notion of wishing to create problems for anyone, and certainly

not for his sister.

He had just started to turn himself around in order to creep back into his room, quite

a startling sight, since, as a result of his suffering condition, he had to guide himself

through the difficulty of turning around with his head, in this process lifting and

banging it against the floor several times.

He paused and looked around.

His good intentions seemed to have been recognized.

The fright had lasted only for a moment.

Now they looked at him in silence and sorrow.

His mother lay in her chair, with her legs stretched out and pressed together.

Her eyes were almost shut from weariness.

The father and sister sat next to one another.

The sister had set her hands around the father's neck.

Now, perhaps I can actually turn myself around, thought Gregor, and began the task again.

He couldn't stop puffing at the effort, and had to rest now and then.

Besides, no one was urging him on.

It was all left to him on his own.

When he had completed turning around, he immediately began to wander straight back.

He was astonished at the great distance which separated him from his room, and did not understand

in the least how, in his weakness, he had covered the same distance a short time before,

almost without noticing it.

Constantly intent only on creeping along quickly, he hardly paid any attention to the fact that

no word or cry from his family interrupted him.

Only when he was already in the door did he turn his head, not completely, because he

felt his neck growing stiff.

At any rate, he still saw that behind him nothing had changed.

Only the sister was standing up.

His last glimpse brushed over the mother, who was now completely asleep.

Hardly was he inside his room when the door was pushed shut very quickly, bolted fast,

and barred.

Gregor was startled by the sudden commotion behind him, so much so that his little limbs

bent double under him.

It was his sister who had been in such a hurry.

She had stood up right away, had waited, and had then sprung forward nimbly.

Gregor had not heard anything of her approach.

She cried out,

"'Finally!' to her parents, as she turned the key in the lock.

"'What now?'

Gregor asked himself, and looked around him in the darkness.

He soon made the discovery that he could no longer move at all.

He was not surprised at that.

On the contrary, it struck him as unnatural that up to this point he had really been able

to move around with these tiny little legs.

Besides, he felt relatively content.

True, he had pains throughout his entire body, but it seemed to him that they were gradually

becoming weaker and weaker, and would finally go away completely.

The rotten apple in his back, and the inflamed surrounding area entirely covered with white

dust, he hardly noticed.

He remembered his family with deep feelings of love.

In this business his own thought that he had to disappear was, if possible, even more decisive

than his sister's.

He remained in this state of empty and peaceful reflection until the tower-clock struck three

o'clock in the morning.

From the window he witnessed the beginning of the general dawning outside.

Then, without willing it, his head sank all the way down, and from his nostrils flowed

out weakly his last breath.

Early in the morning the cleaning-woman came.

In her sheer energy and haste she banged all the doors, in precisely the way people had

already asked her to avoid.

So much so, that once she arrived a quiet sleep was no longer possible anywhere in the

entire apartment.

In her customarily brief visit to Gregor, she at first found nothing special.

She thought he lay so immobile there because he wanted to play the offended party.

She gave him credit for as complete an understanding as possible.

Since she happened to be holding the long broom in her hand, she tried to tickle Gregor

with it from the door.

When that was quite unsuccessful, she became irritated, and poked Gregor a little, and

only when she had shoved him from his place without any resistance did she become attentive.

When she quickly realized the true state of affairs, her eyes grew large, she whistled

to herself.

However, she didn't restrain herself for long.

She pulled open the door of the bedroom, and yelled in a loud voice into the darkness,

"'Come and look!

It's kicked the bucket!

It's lying there, totally snuffed!'

The Samsa married couple sat upright in their marriage-bed, and had to get over their fright

at the cleaning-woman before they managed to grasp her message.

But then Mr. and Mrs. Samsa climbed very quickly out of bed, one on either side.

Mr. Samsa threw the bedspread over his shoulders, Mrs. Samsa came out in her night-shirts, and

like this they stepped into Gregor's room.

Meanwhile, the door of the living-room, in which Gregor had slept since the lodgers had

arrived on the scene, had also opened.

She was fully clothed, as if she had not slept at all.

Her white face also seemed to indicate that.

"'Dad!' said Mrs. Samsa, and looked questioningly at the cleaning-woman, although she could

check everything on her own, and even understand without a check.

"'I should say so,' said the cleaning-woman, and by way of proof poked Gregor's body with

the broom a considerable distance more to the side.

Mrs. Samsa made a movement as if she wished to restrain the broom, but didn't do it.

"'Well,' said Mr. Samsa, "'now we can give thanks to God.'"

He crossed himself, and the three women followed his example.

Gregor, who did not take her eyes off the corpse, said, "'Look how thin he was!

He had eaten nothing for such a long time.

The meals which came in here came out again exactly the same.

In fact, Gregor's body was completely flat and dry.

That was apparent really for the first time, now that he was no longer raised on his small

limbs and nothing else distracted one's gaze.

"'Greta, come in to us for a moment,' said Mrs. Samsa with a melancholy smile, and Greta

went, not without looking back at the corpse, behind her parents into the bedroom.

The cleaning-woman shut the door and opened the window wide.

In spite of the early morning, the fresh air was partly tinged with warmth.

It was already the end of March.

The three lodgers stepped out of their room and looked around for their breakfast, astonished

that they had been forgotten.

"'Where is the breakfast?' asked the middle one of the gentlemen, grumpily to the cleaning-woman.

However, she laid her finger to her lips, and then, quickly and silently, indicated

to the lodgers that they could come into Gregor's room.

So they came, and stood in the room, which was already quite bright, around Gregor's

corpse, their hands in the pockets of their somewhat worn jackets.

Then the door of the bedroom opened, and Mr. Samsa appeared in his uniform, with his wife

on one arm and his daughter on the other.

All were a little tear-stained.

Now and then Greta pressed her face onto her father's arm.

"'Get out of my apartment immediately!' said Mr. Samsa, and pulled open the door, without

letting go of the women.

"'What do you mean?' said the middle lodger, somewhat dismayed and with a sugary smile.

The two others kept their hands behind them, and constantly rubbed them against each other,

as if in joyful anticipation of a great squabble which must end up in their favour.

"'I mean exactly what I say,' replied Mr. Samsa, and went directly, with his two female

companions, up to the lodger.

The latter at first stood there motionless, and looked at the floor, as if matters were

arranging themselves in a new way in his head.

"'All right, then we'll go,' he said, and looked up at Mr. Samsa, as if, suddenly overcome

by humility, he was asking fresh permission for his decision.

Mr. Samsa merely nodded to him repeatedly, with his eyes open wide.

Following that the lodger actually went with long strides immediately out into the hall.

His two friends had already been listening for a while with their hands quite still,

and now they hopped smartly after him, as if afraid that Mr. Samsa could step into the

hall ahead of them, and disturb their reunion with their leader.

In the hall all three of them took their hats from the coat-rack, pulled their canes from

the cane-holder, bowed silently, and left the apartment.

In what turned out to be an entirely groundless mistrust, Mr. Samsa stepped with the two women

out under the landing, leaned against the railing, and looked over, as the three lodgers

slowly but steadily made their way down the long staircase, disappeared on each floor

in a certain turn of the stairwell, and in a few seconds came out again.

The deeper they proceeded, the more the Samsa family lost interest in them, and when a

butcher with a tray on his head came to meet them, and then with a proud bearing ascended

the stairs high above them, Mr. Samsa, together with the women, left the banister, and they

all returned, as if relieved, back into their apartment.

They decided to pass that day resting and going for a stroll.

Not only had they earned this break from work, but there was no question that they

really needed it, and so they sat down at the table and wrote three letters of apology—Mr.

Samsa to his supervisor, Mrs. Samsa to her client, and Greta to her proprietor.

During the riding the cleaning-woman came in to say that she was going off, for her

morning work was finished.

The three people riding at first merely nodded, without glancing up, only when the cleaning-woman

was still unwilling to depart did they look up angrily.

"'Well?' asked Mr. Samsa.

The cleaning-woman stood smiling in the doorway, as if she had a great stroke of luck to report

to the family, but would only do it if she was asked directly.

The almost upright small ostrich-feather in her hat, which had irritated Mr. Samsa during

her entire service, swayed lightly in all directions.

"'All right, then, what do you really want?' asked Mrs. Samsa, whom the cleaning-lady still

usually respected.

"'Well,' answered the cleaning-woman, smiling so happily she couldn't go on speaking right

away, "'about how that rubbish from the next room should be thrown out, you mustn't worry

about it.

It's all taken care of.'

Mrs. Samsa and Greta bent down to their letters, as though they wanted to go on writing.

Mr. Samsa, who noticed that the cleaning-woman wanted to start describing everything in detail,

decisively prevented her with an outstretched hand.

But since she was not allowed to explain, she remembered the great hurry she was in,

and called out, clearly insulted, "'Bye, bye, everyone!' turned around furiously, and left

the apartment with a fearful slamming of the door.

"'This evening she'll be let go,' said Mr. Samsa.

But he got no answer from either his wife or from his daughter, because the cleaning-woman

seemed to have upset once again the tranquillity they had just attained.

They got up, went to the window, and remained there with their arms about each other.

Mr. Samsa turned around in his chair in their direction, and observed them quietly for a

while.

Then he called out, "'All right, come here, then, let's finally get rid of old things,

and have a little consideration for me.'

The women attended to him at once.

They rushed to him, caressed him, and quickly ended their letters.

Then all three left the apartment together, something they had not done for months now,

and took the electric tram into the open air outside the city.

The car, in which they were sitting by themselves, was totally engulfed by the warm sun.

Sitting back comfortably in their seats, they talked to each other about future prospects,

and they discovered that, on closer observation, these were not at all bad, for the three of

them had employment, about which they had not really questioned each other at all, which

was extremely favorable, and with especially promising prospects.

The greatest improvement in their situation at this moment, of course, had to come from

a change of dwelling.

Now they wanted to rent an apartment smaller and cheaper, but better situated, and generally

more practical than the present one, which Gregor had found.

While they amused themselves in this way, it struck Mr. and Mrs. Samsa, almost at the

same moments, how their daughter, who was getting more animated all the time, had blossomed

recently, in spite of all the troubles which had made her cheeks pale, into a beautiful

and voluptuous young woman.

Being more silent, and almost unconsciously understanding each other in their glances,

they thought that the time was now at hand to seek out a good honest man for her.

And it was something of a confirmation of their new dreams and good intentions, when,

at the end of their journey, their daughter got up first, and stretched her young body.

End of The Metamorphosis

By Franz Kafka

Translated by Ian Johnston

Read by Bob Neufeld