Hi,

I am using the Lingq app to learn german language.

My question is about two-part verbs in german language. When I import a text into the app, I couldn’t find a way to recognize these types of verbs and add them to vocabularies. For example “aufpassen“ is a verb that can be separated in two part in a sentence like “Ich passe das Kind auf.” In such case “passen” itself is recognized, but I cannot even manually set it as ”aufpassen” and add it to unknown vocabulary list. I mean regognize the second part in the sentence, say “auf”, together with ”passen”.

Is there anyway to do this?

Thanks for the feedback. Yes, German separable verbs are an issue on LingQ and we have never been able to come up with a good solution for dealing with them. In the end, you just have to learn how to notice them, save both parts and add a separate hint to both words which deals with the meaning when the verb is separated. Not to worry, this is not lost time. The time you spend creating these extra hints and noticing is very valuable and will help you learn. Hopefully, in future we will come up with a more convenient solution but it is a tricky issue for us!

Hi aftech,

the German language is “legendary” for doing this.

For example, even in the “easier” text passages of the German philosoph Hegel (well, “easy” for Hegel, not for regular people like me :-)), the basic sentence structure can be like this:

Infinitive: “hinzufügen” (to add)

Fictive sentence:

Fügen wir … word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word word, etc. hinzu ![]()

This is difficult to digest even for native speakers of German who - as adults- have easily more than 100k hours of constant interactions / immersion in German under their belt.

Today, I’d consider this a “bad” writing style, but the underlying problem is still the same.

Reg. your sentence: "“Ich passe das Kind auf.”

Unfortunately, that’s not a correct sentence because the basic infinitive structure is

“aufpassen auf etwas / jemanden”. So the correct sentence in German is:

“Ich passe auf das Kind / den Hund / die Katze / das Auto / deine Juwelen, etc. auf”.

Basically, that’s a “collocation problem” (that is, highly conventionalized groups of words that frequently go together).

The only solution for language learning is that you should never (apart from the absolute beginner stage) learn single / isolated words, but always collocations / idioms or complete sentences. So you simply mark the whole (short) sentence in LingQ - and that’s your solution!

In short, LingQ has already everything you need to solve this problem by never marking or focusing on isolated verbs (infinitive or not)!

And that’s how native speakers learn their mother tongue as well:

- They never learn it like this:

aufpassen auf - Deine(r) - kleiner Bruder - kleine Schwester - müssen - eine Stunde - jetzt

- und.

- But like this:

“Martin, Du musst jetzt eine Stunde auf Deinen kleinen Bruder und Deine kleine Schwester aufpassen”.

Or to put it differently:

All native speakers are basically sophisticated forms of “parrots” that have acquired tens of thousands of such collocations.

Once we have internalized a few thousands of these “formulaic expressions”, free play with the language starts - and no parrot on planet Earth is able to match that.

But, of course, switching effortlessly between literal speech and metaphors, surfing networks of connotations and associations, etc. is also something that no animal can do. In this sense, human language makes as “special” compared to all other animals - and without it, we would still be the irrelevant primates that our hominid ancestors were…

BTW, if you think that the sentence structure “Fügen wir + filler words (xy times) + hinzu” mentioned above is bad, what about a nasty little variation of it? ![]()

“Fügen wir + filler words (xy times) + subordinate clause 1 with “weil” + continue with main clause - subordinate clause 2 with aber” + continue with the main clause + subordinate clause 3 (why not a relative clause here: der, die, das?) + continue with the main clause, etc."

German is also legendary for such nesting sentences (Schachtelsätze), but long-winded variations are usually considered “bad style” nowadays. However, if you want to know what such sentences look like: just read the books by Thomas Mann, for example ![]()

“Peter, I need a horror example for your last variation!”

Your wish - my command - here it is (you should probably use “deepl.com” for this cutie):

„Und jenseits des Wegknies, zwischen Abhang und Bergwand, zwischen den rostig gefärbten Fichten, durch deren Zweige Sonnenlichter fielen, trug es sich zu und begab sich wunderbar, daß Hans Castorp, links von Joachim, die liebliche Kranke überholte, daß er mit männlichen Tritten an ihr vorüberging, und in dem Augenblick, da er sich rechts neben ihr befand, mit einer hutlosen Verneigung und einem mit halber Stimme gesprochenen ‘Guten Morgen’ sie ehrerbietig (wieso eigentlich: ehrerbietig) begrüßte und Antwort von ihr empfing

URL: Zitate von Thomas Mann (210 Zitate) | Zitate berühmter Personen

Shocking?

Don’t worry, most Germans don’t write like that. Instead, we prefer “sweet and short” sentence structures nowadays.

But is Thomas Mann simply “bad”?

No, he is probably the greatest wizard of the German language that ever lived.

And that’s why he is one of the few Nobel laureates in literature.

In short, he’s simply “on another level” ![]()

If I come across a separable verb, I’ll often add another definition for the base verb and the separable part in parentheses. Or I’ll just add this separable verb form and provide the definition for it. If you look for other’s definitions for a given word, you may already see someone has done this.

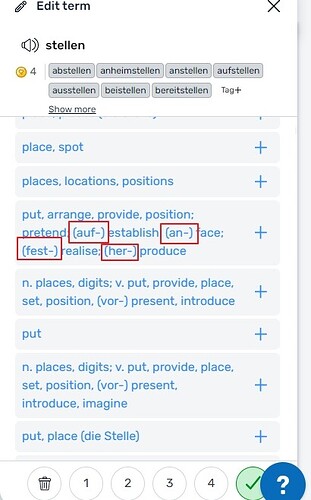

For example, here’s what someone did for the verb “stellen”. As you can see there are many separable prefixes for this word that change the meaning:

You’ll also see with LingQ’s autotagging that some of these additional prefixes for stellen appear in the tags area. If you click these, it will pop open reverso verb conjugation dictionary which also provides the meaning of these (this is auto done by LingQ though, so so far users can’t add this linking).

If the phrase is short, I might save the whole phrase as Peter suggests, but sometimes with very long sentences you may not be able to save the whole thing.

Hi Peter,

Thanks for your kind and complete reply, correction and advise.

For sure learning a word, apart if it is a verb, noun, adjective or adverb, should be done in a sentence to learn the application and grasp the meaning of it.

I would take your advise for sure.